The peaks and valleys of legacy media over the last quarter-century or so can be measured by charting the trajectory of Scott Adams.

In the 1990s and into the new millennium, Adams attained something close to pop culture ubiquity on the strength of the widespread syndication of his comic strip Dilbert in daily newspapers, which, at the time, had retained their historic readership and respect. By the time of the Trump presidencies — as well as the interregnum between the president’s two terms — Adams had been exiled from newspapers for his controversial, sometimes inflammatory statements, but he had already refashioned himself into a personality fit for the more dynamic realm of social media.

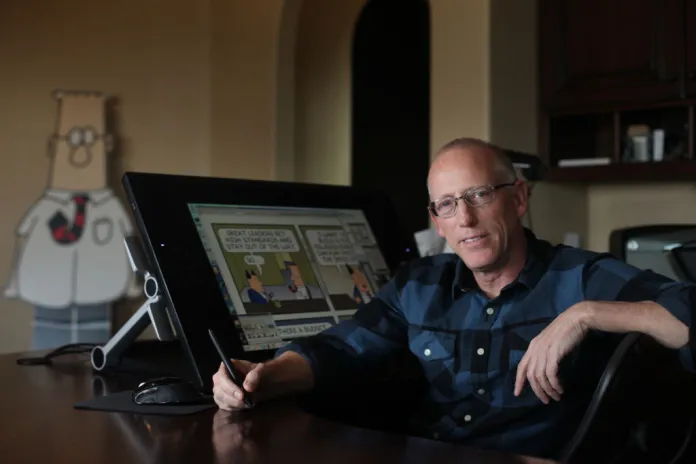

Adams, who died of metastatic prostate cancer on Jan. 13 at the age of 68, was always something of a chameleon. Unlike many of his cartooning forebears, like Charles M. Schulz or Jules Feiffer, Adams did not seem to consider earning a living through pen and ink seriously. Instead, he accepted that his professional fate would be somewhere within corporate America — an experience that, ironically, ultimately fueled the office-based satire of Dilbert. By the end of his life, the comic strip’s popularity had long been in eclipse — as had the relevancy of many of the papers that once carried it — but he had acquired a new set of followers online.

Born in Windham, New York, in 1957, Adams seemed primed to climb the corporate ladder — he majored in economics at Hartwick College and received an MBA from the University of California, Berkeley — until his entrepreneurial gusto kicked in. He was in the midst of a career at Pacific Bell when, with scant cartooning experience, he initiated Dilbert as what would today be called a “side gig.” In 1989, while still drawing a paycheck from Pacific Bell, he created the strip. Even after Dilbert started appearing in ever-greater numbers of newspapers throughout the country, years would pass before Adams evidently felt comfortable to devote himself to it exclusively.

Perhaps only millennials and those older can fully appreciate the extent of the Dilbert phenomenon at its apex. Back then, a syndicated comic strip had the capacity to reach millions, and those millions seized on Dilbert as the next big thing on the funny pages. The strip had the slow-burning wit of Peanuts, the sketchy, low-fi art style of early-era Doonesbury, and a perspective on the American managerial class that was wholly its own. Other strips evoked the more fanciful features of childhood (Calvin and Hobbes) or the messy frenzy of family life (For Better or For Worse), but Dilbert was nonpareil in attending to the trials and tribulations encountered at the water cooler.

Such was the strip’s popularity that it quickly birthed numerous ancillary products, including Dilbert comic strip collections (naturally), Dilbert dolls, Dilbert business books (commencing in 1996 with Adams’s The Dilbert Principle), and, fleetingly, a Dilbert animated series on UPN. There might have even been more such merchandising had the legacy media environment that supported Dilbert not started to fray in the early years of the 21st century. If Adams had put all of his eggs in the basket of his cartooning, he might have fallen off the map.

Instead, Adams seems to have been among the first relatively mainstream, seemingly apolitical figures to perceive an appetite for thoughtful pro-Trump commentary. In the absence of competitors, he began to engage in such commentary himself on his livestreamed program Real Coffee with Scott Adams, which was transmitted on YouTube, Twitter, and other platforms. Here, Adams not only adapted to our era’s preferred form of communication but, arguably, came into his own: with his calm countenance, companionable speaking voice, and generally sharp analysis, Adams expounded for untold hours.

Alas, there can be a cost to speaking provocatively and extemporaneously on the internet: the chance that the speaker will say something foolish, dumb, or downright offensive. Adams arguably did this more than once, but in 2023, he made remarks widely considered to be racist and rightly regarded as indefensible. Dilbert may have already been destined for the dustbin of history, but that destiny was sealed when his syndicate, Andrews McMeel, ceased its representation. Adams transitioned the strip to the Locals platform, but for better or worse, his legacy would be wrapped up with his late-in-life livestreaming.

To his credit, Adams remained an online presence from the time of his cancer diagnosis last spring until shortly before his death. “He was a fantastic guy,” President Donald Trump wrote about Adams on Truth Social this week, “who liked and respected me when it wasn’t fashionable to do so. He bravely fought a long battle against a terrible disease.” Whatever his personal flaws and failings, Adams can be seen as a success story that mirrors his times: from a corporate cog to an influential cartoonist to an internet commentator memorialized by none other than the president.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.