“There are some ideas so absurd,” George Orwell is alleged to have said, “that only an intellectual could believe them.” Intellectuals, the British writer noted, were key to the ascent of some of the most destructive ideologies known to man. But there’s another truth, often overlooked, that helps explain their ascent: privilege. More often than not, the wealthy have played their own role in perpetuating the evils of communism upon the masses.

Discredited long ago, a new breed of politician has reemerged in America championing the idea that real communism just hasn’t been tried. Their very beliefs, outmoded and disproven, are a sign of how removed they are from the concerns of average, everyday working people. And Zohran Mamdani is their embodiment.

Mamdani was elected mayor of New York on Nov. 4. At 34, he will be the youngest mayor to rule Gotham in more than a century. Following a failed career as a rap artist, Mamdani served a mere two terms in New York’s state legislature. He will now preside over not only the largest city in the United States, but what has long been the financial capital of the world.

But Mamdani’s youth and inexperience aren’t the real story. His beliefs are.

Mamdani comes from the Democratic Socialists of America, a formerly fringe, but growing, part of the Democratic Party. Among other things, the DSA seeks the “abolition of capitalism,” the destruction of the Jewish state of Israel, and defunding the police. The DSA’s radicalism is undeniable. The organization condemned the ceasefire between Israel and Hamas that was brokered by the Trump administration and has called for lifting travel restrictions placed on the dystopian dictatorship that rules North Korea.

Mamdani himself has a history of extreme statements, refusing to condemn calls to “globalize the intifada” and meeting with men involved in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. His coalition is explicitly anti-Western. This is the “blame America first” version of the New Left that emerged during the Vietnam War, reincarnated for the TikTok age. As the writer Heather Mac Donald correctly put it, Mamdani “brings the student-activist mindset to City Hall.” One doesn’t need to be Nostradamus to forecast the results.

Mamdani and his ilk have portrayed themselves as fighting for working people. His ally, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), claimed that Mamdani “put together a coalition of working-class New Yorkers.” His victory, the DSA asserted, was “a rejection of the … establishment.”

But neither Mamdani’s backers nor his beliefs are “working-class.” Nor is Mamdani the polar opposite of the establishment. Indeed, he is the wealthy elite that he claims to despise.

Mamdani was born into privilege. His father, Mahmood Mamdani, is a professor at Columbia University with a long history of critiquing colonialism and the West. His mother is a renowned filmmaker who has directed Reese Witherspoon and other Hollywood actors and was even in a position to turn down directing one of the Harry Potter movies. The mayor-elect’s recent wedding was held at his family’s massive Ugandan compound, one of multiple properties they own throughout the world, and took place over three days, complete with armed guards, cellphone jamming equipment, and rows of Mercedes, Range Rovers, and other luxury vehicles. Mamdani’s 2024 rooftop engagement party was held in Dubai and was similarly lavish. These are champagne socialists.

In 2019, the writer Rob Henderson coined the term “luxury beliefs” to describe the “ideas and opinions that confer status on the rich at very little cost, while taking a toll on the lower class.” Luxury beliefs, Henderson argued, are really a way for upper-class citizens to showcase their social status. Previously, the elite used luxury goods to highlight their superiority. But in the era of mass consumption, where the latest product is readily available, “there is increasingly less status attached to luxury goods,” Henderson noted. Accordingly, wealthy elites settled on something else: ideology.

In his final podcast appearance, the late conservative activist Charlie Kirk appeared with Henderson to discuss how Mamdani’s rise is emblematic of the upper crust’s latest fetish. “The very people who back Mamdani,” Henderson pointed out, “are the ones who most resemble him: affluent, overeducated, and eager to prove their virtue at someone else’s expense.”

It would be a mistake, however, to think that any of this is new. Far from being the latest fashion, this trend is but a retread.

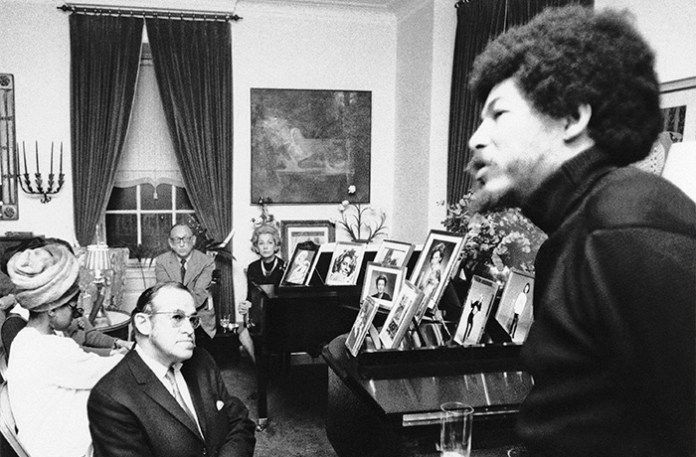

In 1970, the journalist Tom Wolfe coined the phrase “radical chic.” Wolfe was writing about how the famed composer Leonard Bernstein and his actress wife, Felicia Montealegre, hosted a party and reception for the Black Panther Party at their Park Avenue apartment. The fundraiser was for party members who had been charged with conspiracy to murder policemen and blow up four police stations, department stores, railroad lines, an education building, and the Bronx Botanical Garden, among other crimes. In short, it was a fundraiser for men and women credibly accused of terrorism. Bernstein’s wealthy guests lent their support over hors d’oeuvres such as Roquefort cheese morsels and asparagus tips.

Wolfe memorably charged that the party with the Panthers on Park Avenue was itself a sign of privilege. The legendary social critic reached a disturbing conclusion: “There is something so cosseted, so tame, so safe about being very rich that the folks imprisoned in that gilded cage turn their fantasies to the raw, the sexy, the violent.” In short, such beliefs are a status symbol. After all, only the most elite can afford to have them. And it has always been thus.

Long before Mamdani and Bernstein, wealthy elites have been lending their support, financial and otherwise, to destabilizing political movements. One can trace it all the way back to Karl Marx himself.

The author of communism’s seminal text, Das Kapital, Marx’s influence outlasted his 1883 death, inspiring tyrants the world over and causing the deaths of untold millions. Marx claimed to sympathize with the working class. But his own life was far removed from theirs.

As the historian Sean McMeekin pointed out in To Overthrow the World, his 2024 history of communism, “Marx’s social radicalism did not arise from his own economic situation or any unpleasant experience of business or factory life.” In fact, Marx, like not a few of his adherents, was, to use a modern term, a bit of a nepo baby.

Marx was born in Trier, Germany, and was “kind of a perennial student,” McMeekin observed. He had no experience in either business or politics. Instead, he studied philosophy at various European universities, “all the while he was living off of subsidies provided by his father, Heinrich Marx, a successful attorney in Trier, who was increasingly frustrated by his son’s refusal to train for a real profession.” One can readily imagine a modern-day Marx living in his parents’ basement and railing against landowners in angry screeds on Reddit.

When he wasn’t studying philosophy, Marx spent his time writing poetry, frequenting beer halls, and endlessly debating other students. He fulminated against tradition, organized religion, and those who didn’t appreciate his genius. Eventually, he stumbled into journalism, with several wealthy patrons bankrolling his writings. His rhetoric was often angry, bitter, and apocalyptic, advocating overturning the existing order.

Marx began calling for a workers’ revolution without ever having met factory workers, let alone setting foot in a factory himself. “Nor had he done any research on industrial processes or wages, as he would in later years in London,” McMeekin noted. Indeed, Marx “had never shown much interest in the design of factories or worker housing, or the living conditions of laborers.” Rather, “his passions were high theory and high politics, not the nitty-gritty of economics and factory life, which bored him, no matter how much he pretended to be interested in them.”

Yet this lack of experience didn’t stop Marx from pontificating. And it didn’t lessen his smug self-certainty. He knew that he was right, possessing an assuredness that won him both enemies and followers. His early arguments weren’t buttressed by hard data or experience. Rather, they consisted of tautologies and catchy phrases. As McMeekin recounts, in one of his first encounters with factory workers, Marx couldn’t help lecturing them, pounding his fist on the table while labeling them ignorant. He knew what was best for them, and it was their job to learn, follow, or get out of the way. Dissent was heretical.

Eventually, Marx linked with another wellborn socialist, Friedrich Engels, who encouraged him to organize committees of like-minded people. Yet here too, these were largely made up of bourgeois intellectuals, not workers. Marx, reliant on handouts from wealthy patrons and supporters, continued to employ servants. Engels himself helped subsidize Marx’s existence, relying on funds derived from the very capitalist factory system that they resented. In October 1864, Marx and his family threw a formal ball in their new villa, complete with “gold rimmed invitations,” “liveried servants” and a dance band, just as he was “seizing the reins of the International Working Men’s Association,” McMeekin acidly notes. In many respects, Marx was precisely what he railed against. He may have been the first hypocritical communist, but he was hardly the last.

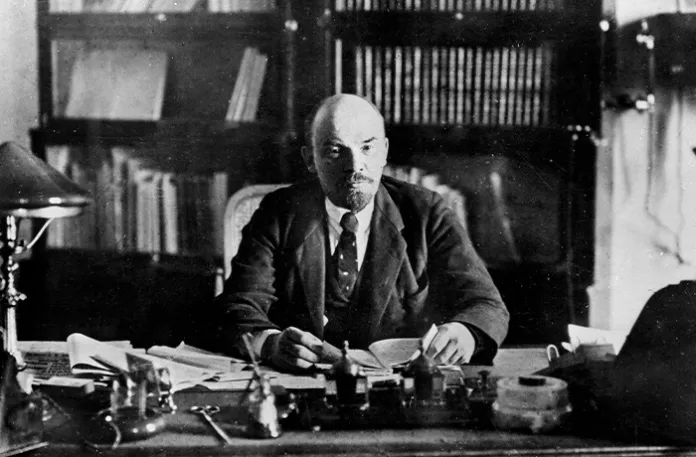

Marx and Engels helped birth communism as an idea. It took both a global conflict and the hinges of fate to make their idea a reality. World War I destabilized the Romanov monarchy in Tsarist Russia, precipitating a revolution that the Bolshevik communists under Vladimir Lenin used to their advantage. Imperial Germany, Russia’s wartime enemy, had sent Lenin, long in exile, into Russia via a sealed train in the very hopes of spreading havoc. As British Prime Minister Winston Churchill memorably wrote, Lenin was “sent into Russia by the Germans in the same way that you might send a phial containing a culture of typhoid or cholera to be poured into the water supply of a great city, and it worked with amazing accuracy.” His entry onto the scene was “the most grisly of all weapons.” Like Marx, Lenin was sure that he was right. And his enemies weren’t just wrong or mistaken. Rather, they were apostates who had to be obliterated.

Most Russians were not communists. From the beginning, communism had to be imposed on the very people it claimed to be helping. Indeed, the Bolsheviks never had anything approaching popular support. What they did have, however, was a keen appreciation for how essential coercion and armed force would be to gaining control. And they relied on actual robbery and foreign funding to maintain it.

Funds from Imperial Germany enabled Lenin and his acolytes to purchase a private printing press, immediately setting about publishing party propaganda in unlimited quantities. Foreign money also paid agitators and demonstrators in the crucial weeks and months leading up to Lenin’s takeover. Seizing private bank assets was one of Lenin’s priorities, and he tasked his new secret police, the progenitor of the KGB, to achieve it. But neither robbery nor foreign largesse could obscure a key truth: Communism doesn’t work.

In April 1920, an American Red Cross commissioner, Col. Edward Ryan, went to Russia to investigate conditions. He found that “Both Moscow and Petrograd” were “indescribably filthy in outward appearances.” And “the streets had not been cleaned for more than three years. … The dirt and rubbish is in all places at least ankle deep and in most places it is up to one’s knees.” Famine was rampant. Ditto for disease. In one hospital that he visited, Ryan was told that “during the previous three months seventy-five percent of the personnel of hospitals had died.” Hospitals lacked basic equipment. So many were dying in Petrograd that “morgues and cemeteries could not cope, and corpses lay around for months waiting to be buried.” By June 1921, the communist newspaper Pravda was forced to concede that approximately 25 million people in Russia’s Volga basin were on the brink of starvation, including millions of children. Secret police reports, unearthed in the 1990s, noted that another 7.5 million Ukrainians were also in imminent threat of starvation. What had sounded so appealing as an academic theory had utterly failed in practice.

To stave off complete collapse, the communists turned to an odd source: wealthy capitalists.

Lenin allowed the American Relief Administration, run by Herbert Hoover, an Iowa orphan, self-made millionaire, and future president, to feed the people he had starved. A number of other Western charity organizations stepped up, feeding 11 million people and providing enough seed for two years’ harvest. In 1921, Lenin introduced his New Economic Policy, a temporary strategy that allowed limited private enterprise and small-scale capitalism in certain quarters. Honest observers might note that it was an implicit admission that communism had failed. But the ideological Lenin never gave an inch, viewing it instead as a pragmatic measure. “The capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them,” he is alleged to have said. And they did.

Throughout the 1920s and the early 1930s, Western companies proved key to building infrastructure in the nascent Soviet state, accomplishing what their communist government couldn’t achieve. As McMeekin noted, “Nearly all of Stalin’s great new industrial works were modeled on or designed by Western capitalist firms.” The Soviets also forged long-standing relationships with capitalists themselves.

Armand Hammer was among the most crucial. Born in New York to a Russian immigrant physician and his wife, Hammer’s parents were communist ideologues who owned five drugstores. Hammer’s father, Julius, lobbied on behalf of the Soviet Union. He also helped launder the proceeds of illegally sold diamonds, which, along with stolen art, were crucial to keeping the Soviet Union afloat in its early years. Julius used his company, Allied Drug and Chemical, to this end. His son, also trained as a doctor, followed in his father’s footsteps. Sent to look after his father’s affairs in Russia, Armand became a courier for the Communist International, which sought to spread communism throughout the world.

As his biographer Edward Jay Epstein chronicled, Hammer and the Soviet state practically grew up together, each enriching the other. Hammer used his medical background as a cover for his early trips to Russia, pretending that he was there to help with the rampant famine and death. Hammer was awarded mining concessions in exchange for his work on behalf of the communist cause. As Epstein noted, the concessions were a part of Lenin’s strategy — what the dictator referred to as “bait.” Lenin “assumed that U.S., British, and German capitalists would vie with one another for the concessions, and to get better terms they would pressure their respective governments to lift restrictions against trading with the Soviet Union.” He wasn’t wrong.

Lenin wanted to use Hammer and other wealthy fellow travelers in the West to shore up the Soviets’ tenuous position. “What we really need is American capital and technical aid,” Lenin told Hammer. For his part, Hammer was captivated by the autocrat. Decades later, he recalled their initial meeting. “If Lenin had told [me] to jump out that window [I] probably would have done it.”

Hammer served the cause for decades, growing wealthy in the process. Hammer’s extensive contacts with the Soviets made him a global player, a fact that he leveraged to his advantage. In his later years, as head of Occidental Petroleum, he became known for his extensive art collection and donations to various charities, including cancer research institutes. Meanwhile, millions of people suffered under the yoke of the dictatorship that he helped save. In many respects, however, Hammer was a pioneer. Others followed suit.

The Chinese Communist Party has constructed the largest and most powerful police state in the history of the world. And, just like their Soviet forefathers, they couldn’t have done so without a great number of wealthy Westerners.

As the writer Lee Smith documents in his new book, The China Matrix, a bevy of Western companies and corporations have cut deals with the CCP, enriching both themselves and America’s foremost foe, gifting Beijing with capabilities and technology that it otherwise couldn’t obtain. “Virtually all of what [China] now makes, from state-of-the-art hi-tech to advanced military hardware, has either been stolen by them or transferred to them by American elites in exchange for future favors,” Smith points out.

The CCP presents the gravest geopolitical challenge that the U.S. has ever faced, with economic and military power that dwarfs previous opponents such as Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and the Soviet Union. And “it was America’s political and corporate elite, the China Class,” Smith calls them, “who largely through trade and financial instruments made this murderous regime what it is today, a peer adversary of the country they call home.” Indeed, the U.S. is now facing the very real likelihood of a conflict with an enemy that it is both beholden to and dependent on — a global shift that profited many elites and which they, not coincidentally, often lauded.

CHINA’S SURGING NUCLEAR THREAT DEMANDS NEW DETERRENCE

“Nothing appeals to intellectuals more than the feeling that they represent ‘the people,’” the late historian Paul Johnson observed. Yet too often, the elite have waged a war on the very working class that they claim to represent. Their very privilege has kept them far removed from the consequences of their fever dreams.

In David Lean’s classic 1965 film, Doctor Zhivago, the protagonist, Yuri Zhivago, confronts a communist military commander named Strelnikov for ordering the burning of a village. “What does it matter?!” Strelnikov asks before noting that the point was made. “Your point — their village,” Yuri memorably replies. Of course, it is far easier to watch villages burn from the safety and comfort of luxurious mansions and villas.

Sean Durns is a Washington-based foreign affairs analyst. His views are his own.