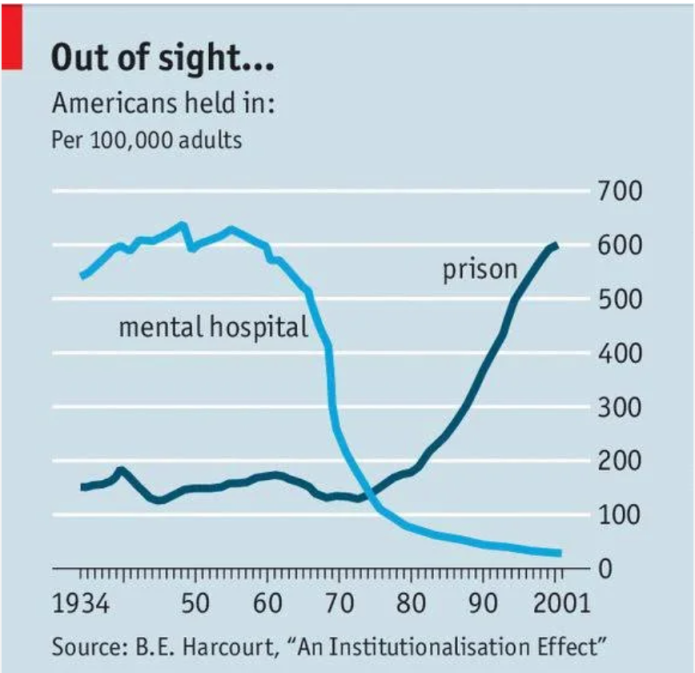

An original black-and-white chart from a 2009 law review article written by Columbia Law School professor Bernard E. Harcourt was colorized by the Economist, and you’ve probably seen it on whatever social media platform you get your news from.

The chart shows the number of Americans, per 100,000, who were held in either prisons or mental hospitals from 1934 through 2001. It shows the number of Americans who were in prison flat and low until the late 1960s, when that number started to rise. The number of Americans who were in mental hospitals is the mirror image, starting out high and flat from 1934 through the 1960s and then falling rapidly as the number of prisoners increased.

“When the data on mental hospitalization rates are combined with the data on prison rates for 1934 through 2001,” Harcourt said, “the imprisonment revolution of the late twentieth century takes on an entirely different appearance: aggregated institutionalization — in other words, the combination of prison and mental hospital populations — is now returning to the elevated levels of institutionalization that the United States experienced at mid-twentieth century.”

The massive rise in our nation’s prison population since the 1960s, in other words, was a direct response to the rise in crime caused by the emptying of our nation’s mental institutions. This policy was embraced by both the Right and Left but is now being rejected by conservatives who want to build more humane facilities for those who are a danger to themselves and others.

And they are being called fascists for adopting a more humane policy.

After decades of pursuing the failed liberal “housing-first” approach to homelessness, which provides housing without requirements for sobriety and treatment, Utah is now switching gears to embrace an “intervention-first” policy. And the key to Utah’s new policy is a 30-acre, 1,600-bed homeless campus being built just north of Salt Lake City.

Most of the residents at the new facility will be there voluntarily. But the facility also set aside 400 beds for civil commitment (people court-ordered into mental health treatment). Those at the facility, both voluntarily and involuntarily, will have access to healthcare, substance abuse counseling, mental health services, job training programs, employment assistance, and housing placement.

It’s a bold plan, one that one activist told the New York Times is like a Nazi concentration camp.

“This idea that it’s compared to Nazi Germany, I don’t understand that level of thinking, it’s just crazy to me,” Gov. Spencer Cox (R-UT) responded. “As if Hitler were to round up people who were dying on the streets, in their own filth, addicted to drugs, and give them the support they need. There is no comparison at all.”

THE MORAL HAZARD OF MONETIZED JUSTICE

“We’re truly a non-compassionate society when we think that compassion is allowing people to die on our streets and to make it unsafe for them and unsafe for everyone else in our communities,” Cox continued. “There is no compassion in that.”

As much as those on the Left, and many on the Right, may wish it to be so, we cannot just let the most vulnerable among us loose on the streets and hope for the best. At some point, they will become dangerous to themselves and others. The real question is how we want to provide the structure they need, through prisons designed for punishment, or facilities such as Utah’s homeless campus, designed to help people be as free as possible.