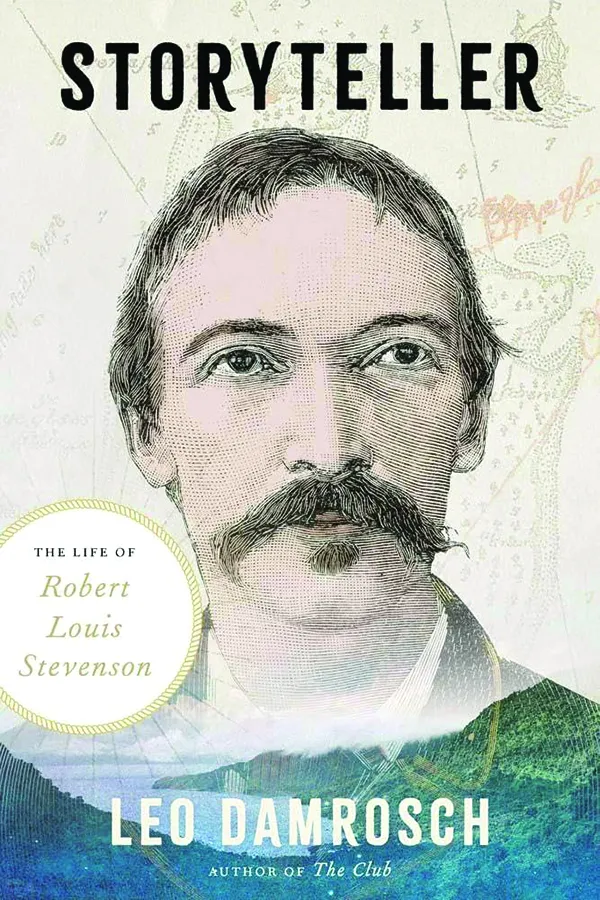

With his tall, thin body and his long arms and legs, Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) looked more like a bag of bones than a world-famous Scottish author. It was his eyes, though, which suggested his literary genius. His friend Mark Twain called them “Stevenson’s special distinction and commanding feature.” His wife, Fanny, said, “Behind them, burned the fires of hell.” In Leo Damrosch’s new biography, Storyteller: The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, he attempts to “reilluminate Stevenson’s unique qualities in their full range and depth.” And for the most part, he succeeds.

Born in Scotland, Stevenson was a sickly child who inherited lung diseases from his mother, who nevertheless outlived him by a few years. He spent many childhood days in bed. One of his poems, The Land of Counterpane, recounts his sick days and shows his imaginative response. His nursemaid, Allison Cunningham, was like a mother to him and played a role in stimulating Stevenson’s imagination. She read him stories and poems focusing on the King James Bible, which had a cadence that inspired Stevenson’s love for the euphony of words, the rhythms of sentences, and the tension found in narratives.

He disliked school and found it boring, but as an avid reader and writer, he educated himself. Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass was his favorite book, and according to his stepdaughter, he read The Song of the Open Road so many times that his copy opened at those pages. When he read the poem aloud, she said, “he put infinite fire and vibrancy into it.”

His parents were fervent Christians. He rebelled and became an atheist, then reconverted. He had a strong moral sense, but he found church services boring. He disliked showy religiosity and thought it had nothing to do with the life and teachings of Jesus, to whom he was devoted. He even wrote prayers that he delivered to his household in Samoa.

He lived at the end of the Victorian era, a time of transition to modernism, beginning his literary career as an essayist and travel writer. Both forms enhanced his fiction, Damrosch suggests, making it seem believable as well as giving it depth. He was most famous for his novels, which include Treasure Island, The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Master of Ballantrae, Catriona, and Kidnapped.

Having come from a family that built lighthouses, Stevenson was expected to take up the trade. As a young man, he traveled frequently, visiting lighthouses and looking for a climate that would improve his health. His father, Thomas, thought that the trips would inspire him. And although he found lighthouses impressive, it was the ocean that inspired him and gave him the desire to travel and to write.

Stevenson visited numerous places in the United Kingdom, as well as Switzerland, France, Italy, and Belgium. He also traveled to the United States, where he enjoyed the mountains in California, as well as talking to his friends, Twain and Henry James, in New York. He went to the South Seas, where he truly found a climate that agreed with him. There, his penchant for writing light travel essays and romances changed into arguments against colonialism and for human rights.

His views deepened as he read Henry David Thoreau and Whitman. Their individualism and love of nature inspired him, and he included them in his book, Familiar Studies of Men & Books.

One of his earliest books, Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, is set in France, which he visited when a love affair took an unhappy turn. Treasure Island, his first novel, is set on an imaginary island, but it draws on Stevenson’s memories of California’s redwood trees and the surf of Monterey. Although highly successful, Treasure Island cast Stevenson as a writer of boys’ adventure stories. But his work was much more complex than that, Damrosch convincingly shows.

Stevenson’s essays were frequently published by the Cornhill Magazine, edited by Leslie Stephen. Ironically, Stephen’s daughter, Virginia Woolf, and her husband, Leonard, were part of the Bloomsbury group, which disdained Stevenson’s writing, considering it shallow. But others, such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, J. M. Barrie, James, George Meredith, and Twain considered Stevenson to be among the world’s greatest authors. So did Jorge Luis Borges, who collected and published an anthology of Stevenson’s work.

The best sections of this biography include Stevenson’s reflections on writing, which, if nothing else, show that the Bloomsbury writers were wrong in their assessment of his work as superficial. Stevenson had an intense devotion to his craft: his stepdaughter noted in a letter that Stevenson arose before everyone else and blocked out about four hours of time for uninterrupted writing. He believed that there should be no unnecessary words. “You carry the hearer to the end without letting him drop by the way,” he said. Stevenson revised his work numerous times — polishing his sentences, carefully designing his plots, and developing his characters. He could make his narratives “alive and compelling,” according to Damrosch, “introducing enough context to keep the reader oriented without bogging down in detail.”

As Stevenson lay dying at the age of 44, his mother and wife rubbed his arms with brandy. The doctor who attended to him looked at his bony hands and arms and wondered aloud how they could have produced such masterpieces, a comment that Stevenson’s mother, Margaret, found insulting. “He has written all his books with arms like these,” she said.

Diane Scharper is a frequent contributor to the Washington Examiner. She teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Institute.