The reports of communism’s demise have been greatly exaggerated, argues historian Sean McMeekin in his new book To Overthrow the World: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Communism. Sure, the Cold War ended more than three decades ago. The Berlin Wall fell, and a mere two years later, the Soviet Union itself collapsed. Communism, it seemed, was over. The West and capitalism had emerged triumphant. The United States stood as the world’s sole superpower, its beliefs seemingly omnipresent. But that was then.

And this is now: The West is under siege, and the American-led world order looks to be fraying. North Korea, a prototypical communist state, has nuclear weapons. Russia, ruled by an unapologetic ex-KGB agent and his gangster cronies, seeks to remake the map of Europe. And the Chinese Communist Party, engaged in the largest military buildup in modern history, is seeking to become the preponderant power in the Indo-Pacific, the region that will soon account for the majority of the world’s GDP.

To Overthrow the World explains how this came to pass. Far from being a relic of the past, communism has an enduring appeal that, McMeekin notes, can be traced to the desire for material or social equality — a desire that dates to antiquity. But it took the French Revolution to birth it.

François-Noël “Gracchus” Babeuf was once a clerk managing manorial property rolls until the revolution presented him with an opportunity. “What is the French Revolution?” Babeuf asked, “[but] an open war between patricians and plebeians, between rich and poor.” Radical even by the standard of the revolution, Babeuf was guillotined for sedition on May 27, 1797. Yet, his radicalism would live on. Babeuf’s co-conspirator, Philippe Buonarroti, would go on to publish a memoir-history mythologizing his “Conspiracy of Equals,” inspiring Karl Marx, among others.

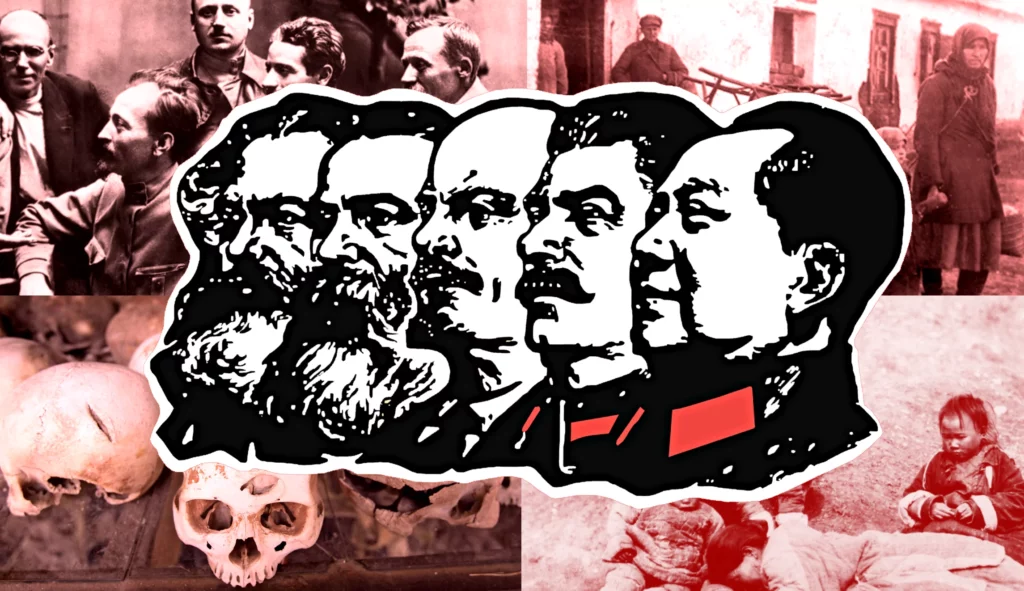

It is Marx who did the most to define communism doctrinally and also to live out its contradictions. Born into wealth, Marx spent his youth in relative leisure, traversing informal social clubs, many at beer halls, where he discussed philosophy and wrote long pamphlets. To the extent that Marx interacted with members of the working class, it was when they were serving him beer while he and his fellow students debated Hegel. As McMeekin points out: “Marx’s social radicalism did not arise from his own economic situation or any unpleasant experience of business or factory life.” The young theorist began writing about proletarian revolution without ever having set foot in a factory or studying wages or industrial processes.

McMeekin highlights how out of touch Marx was with those he claimed to be advocating. Marx “had never shown much interest in the design of factories or worker housing, or the living conditions of laborers.” Rather, “his passions were high theory and high politics, not the nitty-gritty of economics and factory life, which bored him, no matter how much he pretended to be interested in them.” In practice, Marx often looked down on workers. When French and English unionists wrote a founding mission statement in 1864, Marx had it rewritten, telling his partner Friedrich Engels, “If possible, not one single line of that stuff should be allowed to stand.” If Marx’s greatest legacy was as a rhetorician rather than an organizer, however, he was quite a rhetorician. His tracts like Das Kapital and The Communist Manifesto (written with Engels), among others, would inspire generations of communists. But unlike Marx, many of his followers would go on to hold real power — always with devastating results.

Vladimir Lenin was a devoted disciple of Marx. But unlike his intellectual forefather, Lenin evidenced a skill for organizing and a keen political cunning that allowed him to best his rivals. Lenin believed that communism could gain a foothold most readily in a country that had suffered a military defeat or that was gripped by civil war. Lenin thus “aimed to transform politics into warfare,” McMeekin observes. It would take a war, in this case, World War I, to create the upheaval necessary for communism to take root. That war, along with fateful decisions by Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and the subsequent Kerensky government, gave Lenin the opportunity that he was looking for. Nonetheless, it took outside forces, in this case, backers in Imperial Germany and copious amounts of Western naivete, for Lenin to come to power and create the Soviet Union. Lenin was “fortunate in his enemies.” As McMeekin points out, from the very beginning, communism had to be imposed on the very people it claimed to be helping. Communism has, without exception, required armed force and coercion to be maintained.

From its onset, it was a failure as a political and economic model. “We cannot run an economy. This has been proved in the past year,” McMeekin quotes a frustrated Lenin saying in 1921. Some revisionist accounts have portrayed Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin, as the man responsible for turning the Soviet Union into a benchmark for authoritarianism. This was the claim of Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, as well as later Soviet leaders like Mikhail Gorbachev, and not a few Western intellectuals. But as McMeekin makes clear, Lenin was responsible for building the foundations of the monstrous system that Stalin would later perfect. It was Lenin, not Stalin, who created the feared secret police that proved essential to maintaining communist rule. McMeekin also highlights how, from its inception, communism was about theft. Outright robbery and extortion played key roles in the Soviet Union’s rise, with bankers held hostage and, in some cases, murdered so Lenin’s coffers could be filled.

Soon, communist rule would spread to other lands, always via force. The peoples of Eastern Europe, China, North Korea, Cuba, Vietnam, Cambodia, and elsewhere would become hostages and slaves. The butcher’s bill is hard to quantify, but some of the facts McMeekin describes provide readers with a sense of the scale of communism’s effects: Fifteen thousand citizens were murdered in the first two months of Lenin’s Red Terror alone — two times as many as had been murdered by the czarist government in the entire century that preceded 1917. Four years later, even Pravda, the Soviet Union’s newspaper, admitted that 25 million people were on the brink of starvation. In 1922, one foreign observer noted that in Odessa, “hundreds of corpses daily were taken off the streets — many partially eaten by dogs.” Millions of Ukrainians would starve to death in the Holodomor, the victims of a government-induced famine. Cannibalism was not uncommon, including in early gulags where, in desperation, some hungry deportees ingested raw flour. Some, as a result, “choked to death.” By 1937, the Soviet census came in at 162 million people, 15 million lower than expected. Stalin promptly had the census board arrested. Welcome to the worker’s paradise. Slave laborers, including children working 12-hour shifts, helped construct key infrastructure, with larger projects, such as hydroelectric plants, often being built via contract by Western capitalist firms as the Soviet Union itself lacked the engineering means. The horrors would be repeated elsewhere. During China’s so-called Great Leap Forward, a minimum of 30 million people would die.

With vivid prose, McMeekin punctures many myths of communism here, offering a look at a governing system that, in practice, has resulted in mass murder without exception. This is history as a warning. And today, with the Chinese Communist Party challenging the West for primacy, it is not just history. To read To Overthrow the World is to learn that we dismiss the dangers of communism at our peril.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Sean Durns is a Washington D.C.-based foreign affairs analyst.