What would happen if we took constitutional originalism not just seriously but literally?

To answer that question, look no further than The Year of Living Constitutionally, the writer A.J. Jacobs’s hilarious, cringe-inducing, balanced, sincere, and ultimately inspiring attempt to embody our founding document in the context of its time.

As a sort of sequel to his 2007 book The Year of Living Biblically, for which Jacobs spent 12 months adopting the garb, eating habits, and injunctions of the Hebrew Bible (bushy beard, “stoning” adulterers with pebbles), the author’s latest undertaking seeks to absorb and apply the practices, mores, and worldview of the Constitution and its drafters. Instead of the living Constitution, Jacobs gives us living the Constitution.

Jacobs’s ground rules are simple, if not always consistent. “I’ve pledged to try to express my constitutional rights using the tools and mindset of when they were written in 1787,” he explains in his introduction. “My plan is to be the original originalist.” He thoughtfully and fairly takes up the debate over actual originalism (more on that anon), but he arrives at his conclusions through practical (and often deeply embarrassing) experimentation. And he begins by setting ground rules that require him to follow all state and federal laws as publicly understood at the time of their enactment, to restrain his use of 21st-century contrivances, and to “alert others when they do something that would not be protected under an ultra-originalist interpretation of the Constitution.”

Some of his uproarious hijinks seem designed deliberately to mortify his wife and children, who are good sports throughout the yearlong endeavor. He drags his family to a Revolutionary War reenactment in Fort Lee, across the George Washington Bridge from Manhattan, where he’s persuaded to enlist in the Third New Jersey Regiment and “dies” in battle. He quarters a solder in his Upper West Side apartment, then firmly but politely evicts him in keeping with his Third Amendment rights (but not before enjoying a Madeira toast urging America’s enemies to “have cobweb breeches, a porcupine saddle, [and] a hard-trotting horse”). He tries to reintroduce, in all 50 states, the “election cake,” a staple of the early voting experience; one 1796 recipe for this unappealing cake included cloves, raisins, and nutmeg. And he tries to persuade Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) to issue him a letter of marque allowing him to privateer on the high seas.

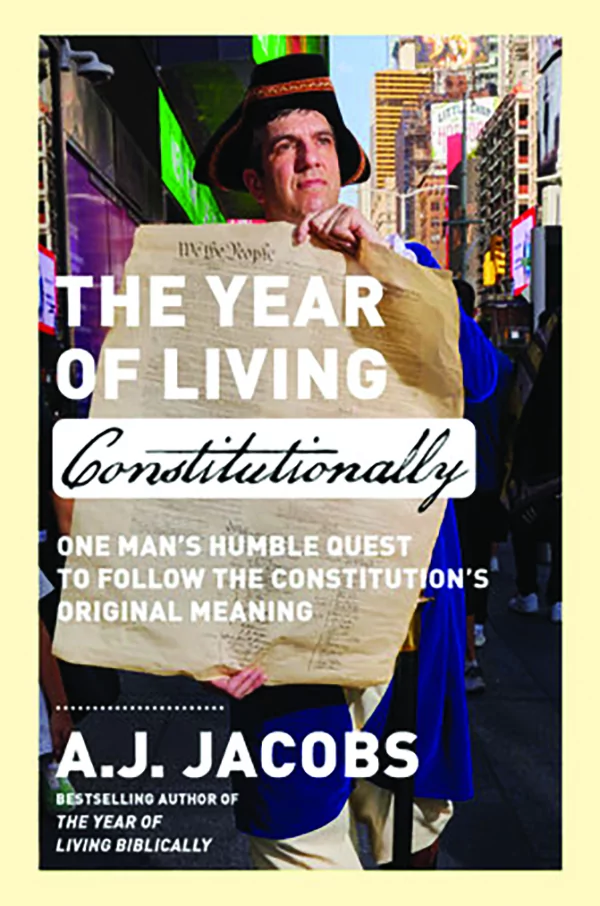

Then there are the sight (and sound) gags, such as the goose quill he insists on writing with (including to sign restaurant checks), or the tricorne hat he wears everywhere, from Times Square to dinner parties (sometimes accompanied by a semiauthentic bluecoat, stockings, breeches, and a period-appropriate musket, which elicits “quite a few angry and/or baffled stares”). He writes pamphlets that he tries to distribute in downtown New York and petitions the government for a plural presidency, and hilarity ensues when he spills ink on the carpet of Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR). He abjures profanity (charging his family members 37.5 cents for every “damn”) and refrains from “seditious speech.” He visits his polling place and insists on voting viva voce — out loud, as was common until the mid-19th century. He pays for vegetables with gold and silver ducats, and he reads aloud the 18th-century equivalent of dad jokes.

But more seriously, Jacobs musters the evidence of his originalist experiment in consideration of its namesake doctrine, now the dominant form of constitutional interpretation. And despite (or perhaps because of) being a layman, he educes a surprisingly open-minded tour de horizon of the constitutional landscape, airing the strongest arguments for and against originalism. Some opponents of the doctrine that he cites are not serious scholars, but he gives a fair hearing to Michael McConnell and Randy Barnett, two of today’s leading originalist scholars. However, he might have considered the Supreme Court’s recent Bostock opinion, in which dedicated originalists like Justices Neil Gorsuch and Samuel Alito ruled in diametrically opposed ways on whether the 1964 Civil Rights Act protects gender identity, as proof that the doctrine itself is capacious and multifaceted.

Jacobs’s treatment of the Second Amendment is similarly sensitive, possibly a result of all that musket training, as is his critical examination of the administrative state, which includes his fruitless attempt to find drinking water unregulated by arguably unconstitutional federal agencies. And he explores both sides of the debates over abolishing the filibuster, the Electoral College, the Senate, Washington, D.C., as an independent entity — and even voting in its entirety. (He entertains a proposal to simply choose our representatives by lottery, channeling William F. Buckley’s famous quip about preferring to be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone book than by the Harvard faculty.)

But perhaps most importantly, Jacobs urges everyone to emphasize and adopt the best aspects of our founding covenant. Thus, regarding slavery, he rightly observes that the Constitution assiduously avoids using the word “slave,” referring instead to “Person[s] held to Service or Labour.” He argues that our founders “knew enough to be ashamed, but they still failed to abolish it.” He examines the fierce debate between the arch-abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who burned copies of Constitution as “the work of a corrupt slavocracy,” and Frederick Douglass, who saw in our founding document the “seeds of freedom,” and Martin Luther King Jr., who regarded it as a promissory note. “There is something to be said,” Jacobs concludes, “for focusing on the Constitution’s promise of freedom and equality instead of its ugliest sections.”

In the end, Jacobs’s book is a love letter to our founding document, an ode to a covenant, a charming, amusing, and much-needed reminder that the Constitution’s core values, nuanced as they are, remain a source of profound national strength — a lesson well worth living indeed.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Michael M. Rosen is an attorney and writer in Israel and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.