How The Dirty Dozen was made

Peter Tonguette

With his incorrigible cynicism and insatiable taste for trashiness, the director Robert Aldrich enthusiastically rejected the pieties that are too often synonymous with Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Aldrich, who was born in 1918 and died in 1983, rejected the transcendent poetry of John Ford, the consoling humanism of Jean Renoir, and the companionable friendliness of Howard Hawks. Instead, Aldrich made movies that revealed the depravity within every decaying child star (What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?). He proposed an equivalence between football heroes and incarcerated felons (The Longest Yard) and between police officers and prostitutes (Hustle). And he strongly suggested that rough-and-tumble female wrestling was no more degrading than anything else in this fallen world of ours (…All the Marbles).

TRAFFIC: GENIUS, RIVALRY, AND DELUSION IN THE BILLION-DOLLAR RACE TO GO VIRAL BY BEN SMITH REVIEWED

If, as Roberto Rossellini once said, Charlie Chaplin’s mercurial masterpiece A King in New York is “the film of a free man,” Aldrich’s entire filmography represents the work of a free man. He was never freer than when he made his 1967 World War II classic The Dirty Dozen.

The film stars Lee Marvin as Maj. John Reisman, an OSS officer attempting to corral a cadre of lawbreaking soldiers for a suicide mission. A box-office sensation upon its release in the summer of 1967, the film was a leading indicator of an emerging antiwar ethos, although its exemplars were not hippy-dippy dropouts. Charles Bronson, John Cassavetes, and Telly Savalas, among others of the “dozen” fighting felons celebrated in the film, were studies in unkempt, untamed manliness — brutes who happened to be on the right side of history.

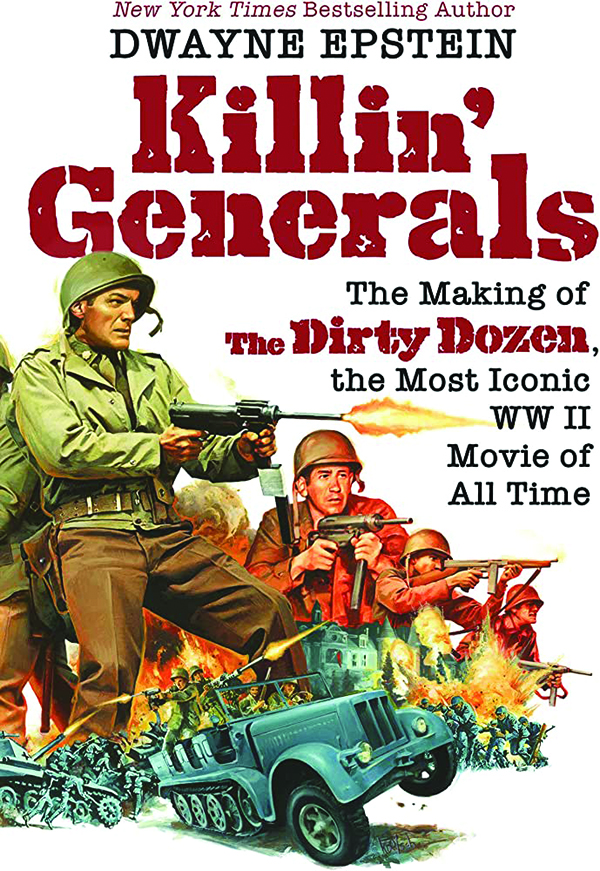

The story of the film — and its intriguing sociological context — is well told in Dwayne Epstein’s new book Killin’ Generals, the title of which is taken from a line given to Bronson after he and his chums lay waste to a French chalet full of Nazis: “Boy, oh boy: Killin’ generals could get to be a habit with me.”

For his part, Lee Marvin understood the dichotomy at the heart of the film’s vision: What the “Dirty Dozen” was doing was right, but that rightness was not prettied up by noble screen heroes like Jimmy Stewart or John Wayne. “Life is a violent situation,” Marvin said. “Let’s not kid ourselves about that.”

The book makes helpfully clear the inconvenient truth that there were plenty of rough types who fought for God and country in World War II. That included future sexploitation director Russ Meyer, the maker of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! who gave Dirty Dozen novelist E.M. Nathanson the notion that some faction of Army prisoners had been promised commutation of their sentences “if they agreed to parachute behind enemy lines before D-Day.” Nathanson borrowed the premise and spun a novel out of it. “I was excited by the dramatic possibilities of these men in that situation,” Nathanson said.

The novel all but invited an unvarnished cinematic treatment of the “Good War.” But how close it came to getting fouled up in the usual Hollywood manner: The first director assigned by MGM to make the movie was one George Seaton, whose credits included Miracle on 34th Street. Santa Claus behind enemy lines? No thanks.

Fortunately, producer Kenneth Hyman turned to Aldrich, who recognized the limitations and essential squareness of the project as it had been developed to that point. “It has a 1940s flavor and a 1950 point of view,” Aldrich wrote to Hyman. “We’re talking about cancer, not ice cream, because today, war is cancer.”

And that’s what Aldrich gave us. Epstein’s book delights in the real-life rebels who came to populate the cast, including Marvin, celebrated here for his role in Don Siegel’s The Killers and his memorable send-off to Angie Dickinson’s character before taking her life: “Lady, I just don’t have the time.” Former Cleveland Browns fullback Jim Brown, also in the film, relished the chance to differentiate himself from African American icon Sidney Poitier: “He had arrived, but he was not an action star. He was not a superhero. Not a loner. He was kind of a nice guy. I wanted to do all the things that we’d never done before in films.” Aldrich encouraged the cast to compete for screen time, according to Cassavetes: “Bob used to call us ‘the animals,’ more like a football coach than a maestro. He’d say, ‘Who wants to do this?’”

MGM promoted the movie like a teenage boy’s fantasy. The poster read: “Train them! Excite them! Arm them! … And then turn them loose on the Nazis!” Ads were taken out in everything from Playboy to American Legion Magazine. Some leading critics clutched their pearls. In the New York Times, Bosley Crowther accused the picture of “encouraging a spirit of hooliganism that is brazenly antisocial.” Dissenting voices came from unexpected sources. “It is an anti-war picture, and should be received as such by thoughtful churchmen,” wrote a critic in the Christian Advocate, and the New Yorker rightly regarded it as “neither anti-war nor pro-war but merely a replica of war.”

Perhaps the audiences who responded to The Dirty Dozen were merely out for a good time at the movies. Perhaps the same can be said of the popularity of the movie’s various progeny, including Kelly’s Heroes, the TV series The A-Team, and, inevitably, Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds. Yet Aldrich must be credited for making war seem like a nasty, grisly affair, as unpleasant as the unshaven faces of its leads. In its intensity, Aldrich’s dark vision can do the useful work of encouraging audiences to think critically: to slough off the complacency that leads us to accept conventional wisdom and repeat earnest bromides. Read this book about how Aldrich’s classic hit came together, and you may find yourself thinking that, with the world perpetually on the brink, we need fewer Saving Private Ryans and more Dirty Dozens.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.