What policymakers and pundits miss when they call for a ‘new Marshall Plan’

Benn Steil

Last month marked the 75th anniversary of the launch of the Marshall Plan — by any reasonable metric, the most successful aid program in history, as well as the most celebrated of all American diplomatic initiatives. The legislation authorizing large-scale economic aid to 16 nations under what was called the European Recovery Program, passed by Congress and signed by President Harry Truman, led to a remarkable revival in output over the subsequent four years and enabled the recipient nations to resist foreign and domestic pressures to turn to extremist political ideologies — most notably, in the context of the period, communism.

Though it was at the time attacked by both the Right (as socialism) and the Left (as imperialism), its achievements in resurrecting Europe and laying the foundations for Cold War American alliances are taken for granted now. Not surprisingly, there have, over the decades that followed, been repeated calls to launch new “Marshall Plans” for war-torn nations and troubled regions around the globe. Syria and Ukraine are only the most prominent of the many recently proposed beneficiaries.

LEVEL THE PLAYING FIELD FOR INDEPENDENT MEDIA

But what exactly makes a plan “Marshall?” Beyond the spending of big bucks, there is no common understanding. Yet once we begin examining the old, original plan, it becomes clear just how sui generis the geopolitical conditions were in (mainly Western) Europe in the late 1940s, how carefully designed the aid allocation mechanisms were, and how difficult it would be to replicate the Marshall Plan itself. Yet understanding why that is the case provides valuable lessons of its own to today’s policymakers and diplomats.

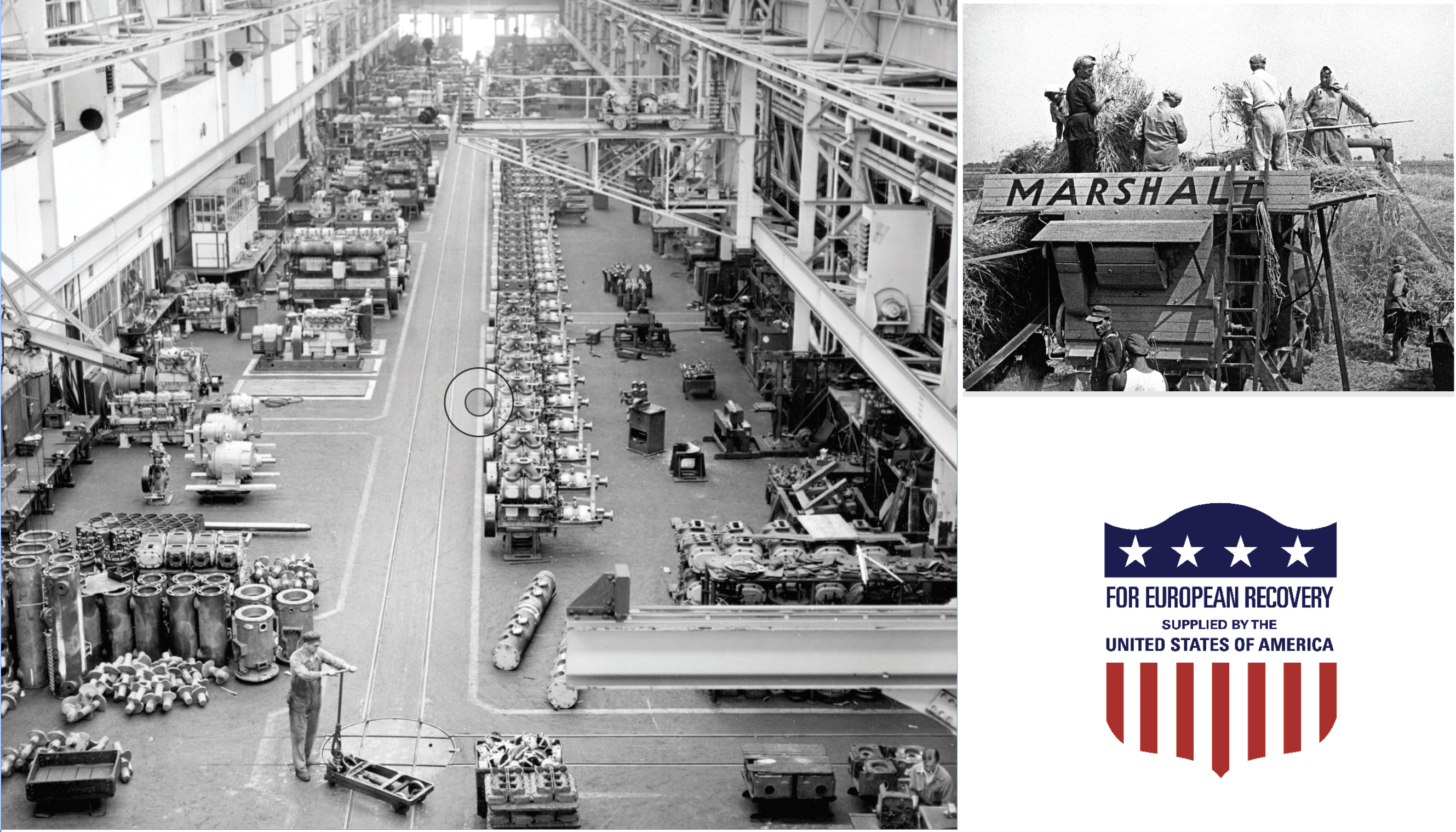

First, let us consider the sums involved. The Marshall Plan dedicated $13.2 billion across 16 recipient countries. This is $165 billion in today’s money. But if we were to launch a Marshall Plan today equivalent in size in terms of U.S. GDP, we would be talking $1 trillion. So the Marshall Plan was large, no doubt. The money was also in the form of grants and not loans, distinguishing it clearly from China’s prodigious “Belt and Road” initiative, which has piled hundreds of billions of dollars of new debt onto nations already heavily in debt.

Yet the Marshall Plan was not, in fact, unprecedentedly large, even in terms of grants. The United States spent $210 billion on reconstruction alone in postwar Iraq and Afghanistan — nearly $50 billion more than the total value of Marshall aid in current dollars. Yet the Iraqi and Afghan aid programs were a dismal failure. The countries have undergone no economic renaissance. Washington achieved virtually nothing politically in Iraq and less than nothing in Afghanistan — which is once again ruled by the Taliban, the same brutal authoritarians who ruled it when the U.S. invaded in 2001.

What, then, accounts for the success of Marshall aid and the failure of much greater amounts of aid after recent wars? In answering that question, we need to be careful about ascribing too much of Europe’s Marshall-era recovery to money. As I document in my recent book The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War, statistical analyses of the aid’s impact suggest that it can account for no more than a modest portion of that recovery. In short, it was not the money alone, or even in large part, that created the recovery. It was, rather, the massive change in the political and security conditions on the ground in Western Europe, wrought by huge changes in U.S. foreign policy, that prompted the revival of private investment and trade that drove the exceptional economic growth over the period. The money provided fuel for the engine of private investment and reason for the masses to shun extremist parties that opposed private enterprise and U.S. aid itself (in particular, the French and Italian communists). But it would never have done much on its own.

The two critical U.S. policy changes were the reversal in German occupation doctrine and a new commitment to underwrite the security of Western Europe.

From September 1944, occupation policy in Germany was widely known as the “Morgenthau Plan.” Named for Franklin Roosevelt’s longtime treasury secretary, Henry Morgenthau, its main element was deindustrializing the country so that it might never again have the manufacturing capacity to threaten its neighbors militarily. By the spring of 1947, as the Marshall Plan was being formulated, it had become clear that the policy was antithetical to stabilizing western Germany and reviving Western European production as rapidly as possible. But the French, in particular, were wedded to the idea of “pastoralizing” their historic enemy.

The price for French and British participation in an American scheme to integrate their economies with western Germany’s was U.S. security guarantees. These were enshrined on April 4, 1949, a year and a day after the signing of the Marshall aid legislation, in the Washington Treaty, NATO’s founding act.

Between 1945 and 1948, U.S. defense spending had plummeted from $963 billion to $95 billion, before turning sharply upward in 1949. The new American security commitment represented a huge shift in the Marshall Plan’s geo-strategy, which had initially been to use economic aid and cross-border integration as an alternative to military engagement in Europe. The aid had been intended to allow the Europeans to provide for their own security against the threat of communism and fascism, both from within and abroad. Instead, Washington was forced to accept that security was a precondition for positive economic and political reform. This is a lesson that was ignored in Iraq and Afghanistan, where it was wrongly believed that security could be managed separately from economic reconstruction and democratization and on a separate timetable.

In 1948, it was not, however, possible to provide credible security guarantees to all European governments anxious to take part in the Marshall Plan. Geography dictated that countries bordering the Soviet Union, such as Czechoslovakia, were at vastly greater risk of successful Soviet invasion than countries further west. And so after Stalin instigated a communist coup in Czechoslovakia in February 1948, with the purpose of keeping the country out of the Marshall Plan, the State Department chose not to intervene. This decision, as uncomfortable as it was from a humanitarian perspective, was necessary to satisfy the fundamental dual objective of the Marshall Plan, which was to secure American vital interests in Europe without having to go to war with the Soviet Union.

Such considerations complicate modern versions of the Marshall Plan. For example, when we speak of the possibility of a “Marshall Plan for Ukraine” today, we must similarly be cognizant of the fact that the country shares over 1,200 miles of land border with a hostile Russia and is therefore incapable of attracting the private investment needed for its successful economic reconstruction and development without either a vast lethal Western military presence or the tacit cooperation of Moscow. Only the latter appears to be remotely feasible or sensible — and even then would require long and disciplined diplomatic engagement. This does not mean those conditions must be present for any aid to Ukraine to have a positive impact, only that geopolitical conditions necessarily limit how much can be accomplished by money alone.

Beyond security, Marshall aid was not just a matter of writing checks but of implementing carefully crafted procedures to affect incentives and distribute risks. “Counterpart funds,” for example, were used to harness the power of economic self-interest on the ground in recipient nations. To access Marshall money, France had to rely on the initiative of its own people. A French farmer, say, would buy an American tractor with his own francs. Those francs were then sent not to the U.S. but to an account managed by the French central bank, to which the French government was required to put in matching funds. The French government was then empowered to use those funds for an economic modernization program agreed in coordination with the U.S. And France, of course, was a highly developed nation with a long tradition of democracy and an impartial and uncorrupted civil service capable of implementing countrywide programs.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The risks of trading with France’s war-torn neighbors, in particular an insolvent Germany, were then eliminated by a European Payments Union underwritten by U.S. capital. Using innovative mechanisms such as counterpart funds and a payments union, the U.S. was able to stimulate investment, production, consumption, and trade in ways in which simple government-to-government transfers never could. Yet I have never heard an aspiring contemporary Marshall Planner speak in terms of actual mechanisms to manage incentives and allocate risks in the specific geopolitical contexts of target recipient nations.

In short, whereas the U.S., the West, and indeed the entire civilized world should be generous with humanitarian and reconstruction aid to Ukraine, we should be under no illusions that that money can generate the sort of rapid and thoroughgoing economic renaissance and embrace of liberal democracy that we witnessed in most Marshall countries after World War II. Prior to the Russian invasion, Ukraine’s GDP per capita was a mere 15% of the European Union average. With no history of a clean and competent civil service capable of instituting a private-sector-led modernization program and, most importantly, with no prospect of securing its eastern borders while Vladimir Putin remains at the helm in the Kremlin, the country resembles the Czechoslovakia of 1948 far more than it does the 16 Marshall nations. The bracing truth behind the success of the Marshall Plan is that we see “success” because of the way the Truman administration chose to define the word in 1948 — that is, by excluding from the Marshall Plan those nations that the U.S. could not protect from the predations of its neighbors without risking World War III.

Benn Steil is director of the international economics program at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author, most recently, of The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War.