Madagascar’s superstitions in American eyes

Rob Long

“Is there any way,” I asked my guide during a recent trip to Madagascar, “that we could visit a local shaman? Instead of seeing more lemurs?”

He shifted uncomfortably. What he wanted to do was show us more lemurs, the gentle monkeylike creatures that populate the island. That’s what tourists come to see, after all.

I don’t really care about lemurs, to be honest. Cute, furry things swinging through the trees? Fun the first time you catch a glimpse of them moving through the forest canopy like a dozen Tarzans. Sort of fun the second and third times, too. But when the fourth set of the fuzzy little charmers swoops through, I’m ready for the next thing. What else you got?

And what Madagascar’s got, aside from a lot of lemurs, is shamans. So my highly educated and city-sophisticated guide eventually relented and took me to meet a genuine Malagasy shaman.

Just to be clear, what we call a shaman is basically what we used to call a witch doctor, but we don’t say that anymore for the same reasons we don’t use a lot of old-school labels — they’re outdated and potentially offensive, and it’s easier to just give in and use the approved term than argue about it. In Madagascar, a more appropriate way to describe a shaman would be traditional healer or spiritual guide, though those New Age-y words don’t really capture the spooky experience of crawling into a dark and smoky hut in the middle of a remote Malagasy village and coming face to face with a young man in a bright red nightshirt. He took me by the hand and held my gaze and peered deep into my eyes, and all I could think was, “Damn, this guy is good.“

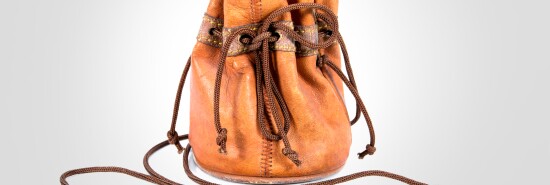

In Malagasy society, shamans are respected and consulted by people from all walks of life, including the educated and the powerful. People come to them when they’re in trouble or want protection. After a consultation, the shaman will often make an amulet, which may be worn around the neck or carried in a bag.

My guide shifted uncomfortably again, and it was then that I noticed the small leather pouch hanging from a cord around his neck, which may have explained his reluctance to bring me there. For the previous few days, he had been all business — a highly Westernized man of science and reason explaining the economic issues facing Madagascar, its complicated history, the habitats of the (many, many) lemurs. The amulet gave him away. He was embarrassed by it but explained that it was for the protection of his family. That made perfect sense. I asked the shaman if he would make one for me.

He was happy to. It’s a business, after all. A shaman gets paid for his magic services — and on a sliding scale, too, it seems, because I was charged the New York City price. As he was collecting seeds and feathers and small bones, he reminded me that he was only offering protection for a certain category of things. This amulet, he told me, isn’t a magic force field that repels all misfortune. Bad stuff can still happen to me, he wanted me to know.

“But not as much bad stuff?” I asked.

“Not as much bad stuff,” was the response, translated by my guide.

As he wrapped up my little pouch, he told me some shamans promise the world. Some tell their clients this or that amulet or spell will solve all their problems. He shook his head. That’s bad business, he said. Only promise what you can deliver.

The amulet now sits next to my bed, and every now and then, I put it around my neck to feel protected against not as much bad stuff.

Yesterday, while I was scrolling through the news on my phone, I read about a politician promising to “create jobs” and another one promising to “save America” — and a magic pill that makes you “feel more confident” and a powder you can mix into your morning coffee that will “activate your brain.” It’s a good thing I’m not superstitious, I thought, or I’d believe all that nonsense, and I touched my amulet for good luck.

Rob Long is a television writer and producer, including as a screenwriter and executive producer on Cheers, and he is the co-founder of Ricochet.com.