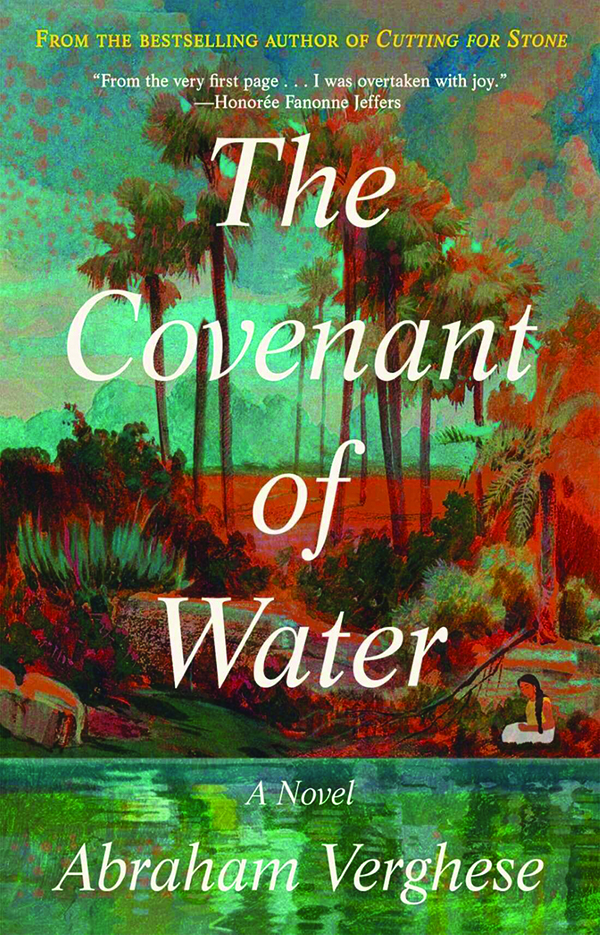

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese reviewed

J. Oliver Conroy

This month, Abraham Verghese — an Indian American physician and writer born in Ethiopia whose 2009 novel, Cutting for Stone, was a bestseller and the toast of many book clubs — has published his second novel, The Covenant of Water. It’s a stunning project: a multigenerational epic that covers the better part of a century of history and casually sweeps from a Scottish slum to the booming city of Madras, now Chennai, and the rural rice plantations of south India.

It seems shocking that a physician and professor of medicine would find the time and energy to write a 736-page historical novel. Then again, literature boasts a long line of doctor-writers, including Anton Chekhov, Mikhail Bulgakov, William Carlos Williams, and Arthur Conan Doyle. (And Doyle’s Dr. Watson was, of course, an army surgeon who first meets Sherlock Holmes while convalescing from a wound in the Second Anglo-Afghan War.)

In interviews, Verghese has suggested that his decision to study medicine was mostly practical. The child of a middle-class Indian family can “either be a doctor, a lawyer, an engineer, or a failure,” he has joked, saying that if he’d been born in America, he might have felt liberated to pursue journalism. But that’s not totally persuasive: Verghese brings the humane, closely observing eye of a physician to his fiction, which is filled with elegant descriptions of ailments and operations; his biography as a doctor seems inextricably intertwined with his literary work.

After Ethiopia’s 1974 coup cut short Verghese’s medical studies there, he and his family came to the United States. He worked for a time as a hospital orderly before deciding to finish his medical degree. As a young doctor in Tennessee, he grappled with the rise of AIDS, which he recounted in his first book, My Own Country, which inspired a television movie by Mira Nair. His second, The Tennis Partner, also a memoir, concerned his friendship with a medical student who died of drug addiction. Verghese is a passionate champion of old-fashioned bedside manner; at Stanford Medicine, where he is “Vice Chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine,” he teaches students to diagnose patients by listening and close examination.

The Covenant of Water opens at the turn of the century in Kerala. A child bride, referred to mostly as Ammachi (“little mother”), has been sent to meet her husband, a gruff and mysterious widower. The characters are members of the region’s ancient Christian community, supposedly founded by Thomas the Apostle and predating the arrival of European missionaries. (Verghese’s own family are Christians from south India.) The writing, in the present tense and gently lyrical, gives a child’s-eye view of Ammachi’s boat journey into the unfamiliar: She sees “a squatting old woman winnowing rice with flicks of a flat basket”; she hears “a boy reading the Manorama newspaper to a sightless ancient who rubs his head as if the news hurt.”

“Push a spade into the soil anywhere in Kerala and rust-tinged water wells up like blood under a scalpel,” Verghese writes. Yet, although the southern Indian coast is a watery land of marshes, lakes, and bays, the bride notices that her new family has a strange phobia of water. In every generation, she learns, at least one person dies by drowning.

The mystery of why is just one of numerous threads running through the novel, which follows the bride’s family, neighbors, friends, and lovers — dozens of characters — from 1900 to the 1970s. The book’s other protagonists include Digby Kilgour, who flees the poverty, classism, and anti-Catholic prejudice of early 20th-century Glasgow by accepting a job as a surgeon in Madras, and Rune Orqvist, a bohemian Swedish doctor who opens a leprosy clinic in Kerala after a religious epiphany.

But that barely scratches the surface. Over the course of the novel’s 736 pages, we learn about India’s Anglo-Indian community, doomed by the Raj to never be accepted as fully British or fully Indian, and the harsh fatalism of the caste system. We experience two world wars, the fall of the British Empire, famine, the electrification of rural India, a smallpox epidemic, the rise of democratically elected communism in south India, incursions by American evangelicalism, and the Naxalite insurgency. All that is delivered in a graceful and painterly prose. An elephant “curls his trunk into a salute.” A character reads a faded document whose “hitches in the loops, coils, and uprights of the Malayalam script” indicate its writing by “old and tremulous” hands. Verghese adeptly captures the charming idiosyncrasies of Indian speech: Describing a polydactyl cat who has given birth to kittens, someone brags, “Babies also six fingers! Good luck only!”; a character who has learned English from Moby-Dick explains how he saved a child suffocating on mucus from diphtheria: “Baby having much white … barnacles in his mouth and throat. Like whale blubber. … I harpooned some and he breathed a little.”

Verghese has a sentimental streak. His characters tend to be virtuous, almost saintly, and there is a slight tone of magical realism that thankfully turns out to be just a tone. (Verghese, the consummate doctor, always returns to the scientific explanation.) Every now and then, striving for lyricism, he forces a simile: “The sky is low and as heavy as wet sheets on a sagging clothesline.” But he has a powerful literary instinct. The world he has created — ornate, plausible, and deeply affecting — is a remarkable accomplishment.

J. Oliver Conroy’s writing has been published in the Guardian, New York magazine, the Spectator, the New Criterion, and others.