West Virginia is the newest DC suburb

Jay Caruso

Driving west from Virginia on the Charles Town Pike and crossing into Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, the elevation provides an expansive view of Charles Town. Then travelers reach the Millville Dam Bridge, which takes them across the hazel waters of the Shenandoah River. With houses dotting the landscape, the lush greenery, blue skies, and the outlying hills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, it’s difficult not to hear John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads” making the drive.

West Virginia is my adopted home. If someone told me, a guy born in Queens, living on Barnett Avenue in Sunnyside, that I’d one day live in West Virginia, I’d have laughed. Though I have lived in five other states since my days in New York (New Jersey, Florida, Georgia, Texas, and Virginia), I never thought Martinsburg would be where I call home.

For several years now, the news centered on people leaving states such as California and New York and settling in Texas and Florida. The former states both lost House seats following the 2020 election, while Texas gained two and Florida gained one. Is West Virginia a growth state as well? No. West Virginia also lost a House seat because its overall population has declined since 2010. However, the eastern panhandle of the state, an area that juts out from the west, bordering Maryland and Virginia and, in some areas, a stone’s throw from Pennsylvania, is a different story.

Berkeley County, where I live, grew 22% between 2010 and 2020. Jefferson County, home to Harpers Ferry, Ranson, and Charles Town, grew by 11%. In 2021, Doug Copenhaver, president of the Berkeley County Council, responded to a question about what contributed to the growth. He said the business-friendly environment, relaxed lifestyle, and proximity to the east coast are all part of it (the eastern panhandle, depending on location, is anywhere from 60 to 75 miles from Washington, D.C.).

The lower cost of living is also attractive. The governor, Jim Justice, and the state legislature passed the largest income tax cut bill in the state’s history. Its top income tax rate of 5.12% now makes it lower than Virginia and Maryland, where residents are subject to separate state and county income taxes. The cost of real estate is another draw.

COVID-19 completely upended the employer/employee relationship, especially with the dynamic of remote and in-person work. Three years after COVID-19 turned most of the United States into a mammoth ghost town, the effect of this unprecedented workforce “disruption,” to borrow the cliche, still lingers. Remote work and hybrid work are common nomenclature for employers and job seekers, and it no doubt factors in people making a move to West Virginia, as it did for me.

When my wife and I began searching for a house, we knew that purchasing in Arlington, Virginia, where we lived, was likely out of the question. According to the real estate website Redfin, the current median price of a single-family home in Arlington County is $640,000, and that is down 1% from a year ago. The median price for a single-family home in Berkeley County, West Virginia, is $289,000, which is a 10% increase from last year.

We lived in a two-bedroom, two-bath, 1,000-square-foot apartment in Arlington, in a terrific building on Columbia Pike near the famous Bob and Edith’s Diner. The fifth floor offered a beautiful view of the street below and the clubhouse of the Army Navy Country Club. Our all-in costs, including rent, water, garbage service, and pet rent, were just over $2,300 per month.

The home we purchased in Martinsburg is on a corner lot, with double the square footage, a two-car garage, a screened-in patio, a deck, and a fenced-in backyard. When we left Arlington, we had two cats. Now, we have two cats and two dogs, and they all enjoy the outdoors. The cost is the same as what we paid for the apartment. In the morning, we wake up to the sounds of birds chirping and the quiet rumble of traffic a mile away on Interstate 81, rather than buses, fire engines, and the beeping horns of drivers on Columbia Pike.

For those who commute to the Washington area for work, the MARC train in downtown Martinsburg offers three departure times in the morning directly to Union Station. Highway routes through Maryland and Virginia provide various means for drivers to get to work. The eastern panhandle is only an hour from Dulles International Airport. I-81 provides access to Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. One could drive through four states in the span of about 40 minutes. Those on the eastern panhandle can visit Blackwater Falls State Park in Davis, West Virginia, one day and the Amish in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the next, both about the same distance. Gettysburg National Military Park is a mere hour away.

The area is rich in history, as well. Martinsburg was established in 1778. Harpers Ferry, 1734, and Charles Town, 1801. Harpers Ferry figured prominently in the Civil War with a battle that took place Sept 12-15, 1862. The garrison was an important part of the Maryland campaign. When Gen. Robert E. Lee invaded Maryland, some of his army, under the direction of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, surrounded and captured the Union garrison, taking control of the area, culminating in one of the most significant surrenders by federal forces during the war and the capture of over 12,000 Union soldiers. Nearby Martinsburg, while not a fixture of any major battles, factored in because of the railroads. Martinsburg was a northern town in Confederate country, literally on the border between North and South. The city reportedly changed hands between the Confederacy and the Union 37 times.

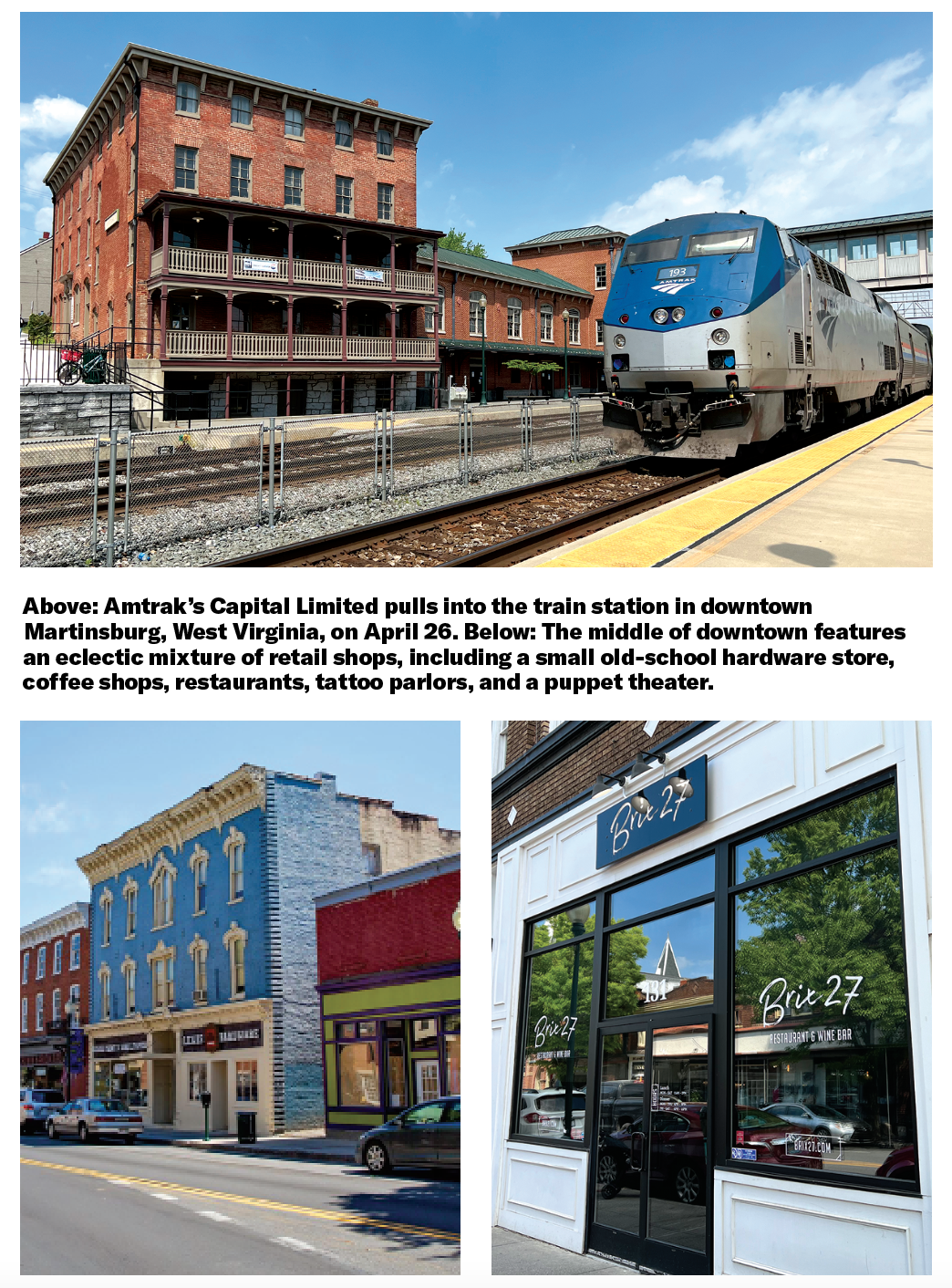

Today, of course, it is entirely different. Downtown Martinsburg has an array of old buildings and homes, some of which built in the 1800s exist on a stretch known as “millionaire’s row.” The middle of downtown features an eclectic mixture of retail shops, including a small old-school hardware store, coffee shops, restaurants, tattoo parlors, and a puppet theater. There is even a used bookstore in an old bank called, appropriately enough, Bank Books.

The people here are friendly and inviting. Neighbors will wave hello as they walk by with their dogs or children. While most people don’t wear their politics on their sleeve, this is undoubtedly Trump country. Along Williamsport Pike, a road that served as the principal thoroughfare to the southern part of town, a resident has a sign up on the fence that says, “Fix 2020 First!” There is often a gentleman on the side of the road during nice weather selling giant Trump flags, and along I-81, after crossing into West Virginia from Winchester, Virginia, someone has a very tall flagpole on his or her property with a flag that reads, “F*** Joe Biden.” And on rare occasions, one can drive past a property that will have a Confederate flag displayed somewhere.

With all the good West Virginia offers, it also has its downsides. While it is a very affordable state, it is also one of the poorest in the nation, with over 17% of people living below the poverty line. The slow death of coal reduced those employed in the industry from over 100,000 to under 13,000 currently, the lowest number since 1890. The opioid crisis has hit the state hard, and it has the highest overdose death rate per 100,000 people in the country by far. With 81.4 deaths per 100,000, it dwarfs Kentucky, which is second, at 49.1 per 100,000. West Virginia has the highest obesity rate in the country. It ranks in the top 10 states for heart disease deaths. It isn’t difficult to spot pockets of poverty here in the eastern panhandle, and some of the more western areas of Berkeley County don’t yet have access to everyday conveniences such as high-speed internet.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Every state has its faults, and West Virginia is no different. Still, here on the eastern panhandle, the growth is noticeable. New small businesses pop up all the time, and because of the central location, it is drawing the interest of developers for warehousing and distribution, similar to its northern neighbor of Hagerstown, Maryland. New housing construction continues despite inflation and higher interest rates, peeling away people from Maryland, Virginia, and Washington who want the homeownership part of the American dream.

The eastern panhandle of West Virginia has become the latest Washington, D.C., suburb.

Jay Caruso is a writer and editor residing in West Virginia.