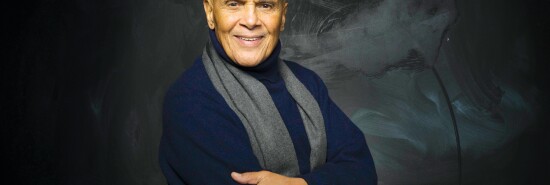

Harry Belafonte, 1927-2023

Peter Tonguette

Harry Belafonte was an emissary from a different era in American entertainment.

The singer-actor-activist, who died on April 25 at age 96, ranged over a multitude of mediums and was captivating in each. As a vocalist, his mega-hit recording of the Jamaican folk song “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” birthed a midcentury mania for calypso, and his performances in such formidable films as Carmen Jones (1954) and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) established him as a leading man of rare grace and force. In the process, he expanded the horizons of African American performers, but he was never content to rest on his show-business laurels.

His obvious integrity and husky authority as an orator made him a natural spokesman for the civil rights movement, which coincided with the peak of his popularity. The same public that invited him into their living rooms with records and TV appearances, and bought tickets to see him in the movies, wanted to hear what he had to say about the issues of the day.

Belafonte was among the stars who participated in the 1963 March on Washington — a famous photograph from the march shows Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, and Charlton Heston, the statue of Lincoln looming over their shoulders, standing side by side — and he was willing to use his own checkbook in furtherance of the cause. Having established a close bond with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Belafonte organized the effort to post bail for the civil rights icon who had been jailed in Birmingham.

Born in 1927 to Jamaican parents then residing in New York, Harold Bellanfanti Jr., as he was known at birth, spent his earliest years there before his mother pulled up stakes to her home country with her children in tow. A teenager by the time he returned to New York, Belafonte served in the Navy, became a colleague of Poitier’s at the American Negro Theater, and experienced his first hint of success through his raspy but resplendent renditions of folk tunes.

Belafonte mined this tradition in his inaugural record, 1954’s Mark Twain and Other Folk Favorites, and brought it to the mainstream with his third outing, 1956’s Calypso, which included “Day-O,” “Jamaica Farewell,” and “Man Smart (Woman Smarter).” A huge hit with listeners, Belafonte churned out record after record during these years: a blues album (Belafonte Sings the Blues), a Christmas compilation (To Wish You a Merry Christmas), and a selection of spirituals (My Lord What a Mornin’).

By then, Belafonte had found a kindred spirit in pushing artistic boundaries: The director Otto Preminger — a noted enemy of the Production Code, blacklist, and Hollywood studio interference — picked the performer to headline his 1954 musical Carmen Jones, a strikingly stylized reimagination of the Bizet opera Carmen whose boldest gambit was neither its long, uninterrupted takes nor its sexual forwardness but its use of an all-black cast (which had also been the case in the 1943 stage version by Oscar Hammerstein II from which the film was adapted). Here, working with iconic black performers, including Dorothy Dandridge and Pearl Bailey, Belafonte proved his bona fides.

Five years later, Belafonte himself was the prime mover behind Odds Against Tomorrow, a notably serious film noir that traded the genre’s superficial trappings, shadow and light and smoky rooms, for a glimpse into an authentic social evil: The film, produced by Belafonte and directed by Robert Wise, starred Robert Ryan as a prejudiced felon who unhappily agrees to cooperate on a heist with a black man, brilliantly played by Belafonte.

Belafonte never lost his appetite for a fight. He was deeply involved in the opposition to apartheid in South Africa. Less nobly, he had kind things to say about Fidel Castro and most uncharitable things to say about George W. Bush; such ill-considered and (worst of all) blandly predictable far-left pronunciamentos were unworthy of a genuine civil rights icon.

Yet, through it all, he retained his ability to connect with an audience. His calypso music got a new lease on life thanks to its unlikely use in Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice (1988), and despite an intermittent screen career after the 1970s, his acting chops proved in good shape when Robert Altman tapped him to play a gangster in a superbly textured film noir, Kansas City (1996).

He was given his due and then some — a Kennedy Center Honor, an honorary Oscar for his humanitarian undertakings — and multiple generations were enriched by his voice, however he chose to use it.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.