The US should help Ukraine dissect Crimea from Russia, not seize it

Tom Rogan

Retaining sufficient stockpiles of man-portable anti-air and anti-ship missiles for a looming defense of Taiwan, the United States should arm and otherwise support Ukraine until Russian President Vladimir Putin recognizes the costs of war outweigh any feasible gains.

Yet, as Russia adopts a static defense strategy and Ukraine prepares for a spring counteroffensive, the question of Crimea is again rising in relevance — specifically, whether the U.S. should support a Ukrainian effort to retake the peninsula. This is not likely to be a hypothetical concern.

RUSSIA MOBILIZATION RHETORIC HINTS AT SHIFT TO STATIC DEFENSE STRATEGY

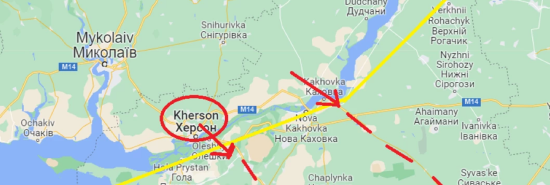

Ukrainian planning is being predominantly shaped by the British Army, which is guiding Ukraine toward more aggressive offensive action than the U.S. military. As I noted last November, Ukrainian interests point toward a southern offensive designed to dissect Russian forces in Crimea from their comrades in southeastern Ukraine. Success in this regard would allow for the likely mass encirclement of Russian forces and an expanded front for follow-on operations against Russia’s bastion in the Donbas. The U.S. should support these efforts with arms and other aid.

That said, I disagree with those who argue the U.S. should arm a ground offensive into Crimea.

Don’t get me wrong; the U.S. should provide political and humanitarian aid for such an effort. The U.S. should also allow Ukraine to use U.S. munitions to strike Russian strategic positions in Crimea from afar. This support is necessary both to degrade Crimea’s viability as a Russian holding but also to limit Crimea’s service in Russia’s broader war effort. Still, if Ukraine wants to conduct a ground offensive into the peninsula, it should do so without U.S. materiel such as armored vehicles and tanks.

Top line: The U.S. must balance Ukraine’s unquestionably legitimate interest in retaking Crimea, its occupied sovereign territory, alongside U.S. strategic interests in Ukraine. U.S. strategic interests entail Ukraine’s eventual victory as well as the mitigated risk of a direct U.S. military conflict with Russia, the mitigated risk of Russia using nuclear weapons, and the mitigated risk of a political conflagration in Moscow that sees an ultra-hardliner replace Putin.

That latter point does not get enough attention.

A successful Ukrainian effort to retake Crimea would constitute an urgent military crisis of deep political import to Putin and the Kremlin. Were Putin removed in such a scenario, however, his most likely successor would not be a centrist compromise candidate but rather a hawk. Nor is it an exaggeration to say that Putin might gamble that his only way to avoid removal would be to use a nuclear weapon against Ukrainian forces. This action would likely not so much be designed to deter Ukraine but rather to provoke a NATO political crisis in which the European Union blinked and demanded an immediate ceasefire. Were a hard-liner such as security council chief Nikolai Patrushev or energy czar Igor Sechin to replace Putin, their ideology and character suggest they would engage in high-stakes brinkmanship Escalation that might include the use of nuclear weapons. This concern speaks to a broader point.

While it is clear that the Kremlin fears rising public concern over the disastrous conduct of the war, the ascendant political constituency in the Kremlin is clearly that of the hawks.

The moderate Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, seen as a tentative reforming influence on taking office in January 2020, now appears to be little more than a weak bureaucrat. Former President and onetime centrist Dmitry Medvedev, a keen follower of the political winds, has morphed into an avowed hawk. And Patrushev passes each week with hyperbolic screeds on the need to prevent the extinguishing of Russian sovereignty under the boot of American colonialism. Putin increasingly echoes Patrushev’s rhetoric.

It’s also important to note that Crimea takes on a special value for Russian elites and Putin personally.

While analysts like Luke Coffey rightly identify the historical separation of Crimea from Russia, they underestimate the philosophical priority that Crimea holds in Kremlin thought. True, the long-enduring Crimean khanate was not part of Russia. But it is also true that the khanate was an effective slave state which, in very significant part, economically sustained and politically defined itself by its relentless capture of Russians for the slave trade. It was, in this regard, the figurative and literal successor to the Mongol Golden Horde that subjugated what is now Russia. The mid-19th-century Crimean War, and the Nazi seizure of Crimea in 1942, similarly humiliated Russia. History matters to Putin, and pride matters to Russians. At the same time, Crimea’s provision of Russian access to the Mediterranean and beyond is part and parcel of Putin’s ambition for a restored “Greater Russia.” Putin wants a Russia that dominates from the Arctic north to the precipice of the Middle East.

Crimea has thus taken on an almost theological value for Putin, something underlined by his increasingly overt attempts to define himself as a modern fusion of Peter the Great and Catherine the Great (who, it should be noted, seized Crimea for the Russian empire). This reality cannot be ignored by U.S. policymakers. Nor, however, should it produce overdue caution of the kind that has seen the Biden administration bow to Russian attacks on U.S. military forces. The Russians respect weakness as much as a shark respects a bleeding seal.

Instead, the U.S. should focus on helping Ukraine drive Russia toward an understanding in which its by-far best option is to offer Ukraine a conciliatory peace. That might, for example, entail a resumption of the 1990s partition treaties under which Russia paid Ukraine for its retained naval access to Sevastopol. But even a dissection of Crimea would serve Ukraine’s interests and cause a major crisis for Moscow. For one basic but critical example, it would allow Ukraine to re-dam the North Crimean Canal and thus restore the Peninsula’s prewar water crisis. Moreover, without a land border, Russian force mobility and resupply efforts would have to rely on water, air, or the Kerch Bridge (which connects the Russian mainland to Crimea). All of those assets would be vulnerable to Ukrainian strikes.

When it comes to Crimea and the war more generally, the key is not to corner the Russian bear but rather to bleed him out so that he must retreat before he perishes.