Bob Dylan’s latest trick

David Polansky

This is one of those reviews that would probably have been better written double-blind, like they feature in academic journals. As with the films of Terence Malick or Michael Mann, Bob Dylan is just someone I can’t really be objective about. I like the Woody Guthrie-aping troubadour stuff. I like the drunken mid-‘60s Rimbaudian stuff. I like the electric aggro stuff. I like the faux-Nashville crooner stuff. I even like the period in the ‘80s when he was dressing like a pimp on Miami Vice and trying to sound like Dire Straits. Naturally, I like his latest iteration as the wizened ambassador of America’s great folk idioms.

He is simply nonpareil. As the critic Bill Wyman put it, “not even The Beatles can compete with the sheer quantity of his essential songs.” All of which is to say he would seem to be the ideal author of his latest book, The Philosophy of Modern Song — a tour d’horizon of the American pop song. I say “seem,” because as always with Dylan, this statement requires immediate qualification. After all, more than any comparable cultural figure, Dylan is (how to put this?) a notorious, inveterate fabulist. It’s no accident that he calls himself “the Joker” in that famous opening line of “All Along the Watchtower.”

First off, the title of the book is a lie. There’s no discussion of any philosophy of music, nor is there the remotest attempt to lay out a systematic treatment of modern popular music. Instead, sans introduction or conclusion, we get 66 (and, gosh, what could the significance of that number be?) disconnected chapters on (mostly American) popular songs mostly from across the 20th century. Each chapter takes a different song as its focus, and these follow no apparent chronological or thematic ordering principle.

Some, but not all, of the entries are bifurcated, with one section mainly written in the second-person point of view (addressed to the artist or the protagonist of the song or the reader or who knows), providing a kind of impressionistic treatment of the ethos of the track in question and written like a carnival barker who has read a lot of beat poetry. The other section appears to offer more of a third-person objective discussion of the track and the artist but will, without warning, veer into discourses on whatever strikes his fancy — the history of Esperanto, the meaning of the vice presidency, and so on. Both sections are basically unreliable.

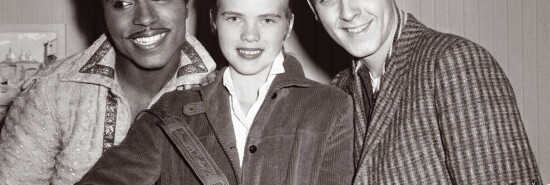

Interspersed throughout is a remarkable collection of reproduced images, which may or may not serve as a sly commentary on the text. Some are just great photos of the artists in their prime. Others are more like visual jokes — like printing Jack Ruby’s mugshot opposite the chapter on “Ruby, Are You Mad?”

Beyond this, questions abound. Why does the book count Dunkin’ Donuts among the dedicatees? Why does the mini-essay on Carl Perkins’s seminal “Blue Suede Shoes” include a digression on Felix Dzerzhinsky, the creator of the Soviet secret police? Why does his discussion of Johnnie Taylor’s rueful soul tune “Cheaper to Keep Her” detour into an expansive defense of polygamy? Is it accurate to describe the great songwriter Warren Zevon as “the tomcat with the stiff penis who pisses gold urine and brings ripples of excitement to stodgy old lives”?

And why these particular songs anyway? It’s not a canonical treatment of modern rock and pop — no Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Beatles, Stones, or James Brown. Some early reviews and press releases have described these songs as a list of Dylan’s favorites, but that’s not made explicit anywhere in the text. And even if it were, how much credence could you give it? For while certainly idiosyncratic, it’s hard to gauge how significant many of these songs are to him personally. Key influences, such as Woody Guthrie and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, are missing, as are many of those near-contemporaries he played with, including Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, and most of all, The Band.

Occasionally, we do get something like straightforward commentary, and it’s frequently insightful and sharp: in his recognition of what made the Grateful Dead’s sound distinctive or his appreciation for Ry Cooder’s musical contributions to other artists’ records. For a guy who made his name singing some of the most vituperative songs ever recorded (“Positively Fourth Street,” “Idiot Wind,” etc.), he’s not shy with praise. And of course, the descriptions are gold. Of Jimmy Reed: “There’s no city concrete beneath his feet.” Bluegrass is “speed metal without the embarrassment of Spandex and junior high school devil worship.” They’re also laugh-out-loud funny — like when he says in a throwaway line about George Jones that “when a guy who rides his lawn mower to the liquor store because his wife hid the car keys is more dependable [than his musical rivals], you have a sense of what country music was like at the time.”

Every once in a while, he’ll drop all pretense and hit you with a line that just stops you short, like the arresting valedictory sentence of his chapter on Sonny Burgess: “This is the sound that made America great.” Perhaps we should take these moments at face value. Anyone who listened to Dylan’s old (fantastic) radio show can attest to the sincerity of his love for the deep tributaries of American music and to his ability to make surprising connections across form and genre. Maybe this volume is more like a literary version of The Basement Tapes, where irony and sincerity and ancient and new-under-the-sun are so intertwined you can’t pull them apart.

If there is an agenda at work behind this kaleidoscopic collection, it seems almost … conservative? The majority of the recordings date from over a half-century ago, the earliest from 1924. In a neat bit of Dylanesque perversity, the latest is from 2004 — but it’s a recent recording of a Stephen Foster tune, first written over 170 years ago. The whole volume is shot through with references to old movies, radio technology, steam trains, and other outmoded forms of transportation.

Like Lucinda Williams or Les Blank, he is passionately, obsessively localist — concerned with the particular distinctiveness that can only be found in those vanished or vanishing corners of America that have not yet been steamrolled by cultural cosmopolitanism and economic free-marketism. He pejoratively describes the subject of the Eagles’ “Witchy Woman” as “the woman from the global village of nowhere — destroyer of cultures, traditions, identities, and deities.” (The rest of the description is unprintable on these pages.) One is reminded throughout of T.S. Eliot’s line: “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” Dylan’s fragments are classic cars, film posters, old ‘45s, mythic tall tales of America.

That said, at this point, it’s hard to know what level of meta he’s really operating on. He is famously a throwback to the “old, weird America,” but here, he is acting as its archaeologist as well — as though his own music weren’t part of its strata. He’s canny about it, too. Check the deadpan with which he casually asserts that Elvis Costello clearly “had a heavy dose of ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues.’” Similarly, you might get all the way through his short chapter on Johnny Cash’s mighty “Big River” before remembering that his relationship with the subject is unlike almost anyone else’s. After all, most of us haven’t recorded with Cash himself or had him write a poem about us (those are Cash’s words adorning the back cover of Nashville Skyline).

The alert reader will have noted by this point that I have not actually reviewed the book in any conventional fashion. That’s because I’m not a mark. I’m also not going to review Orson Welles’s broadcast of War of the Worlds. What is there to say about a book that makes you keep checking over your shoulder? Should you buy it? What kind of question is that? I just told you that Bob Dylan wrote a book on music. Yes, you should buy it. You should also enroll in a basketball camp with Michael Jordan, if that becomes available to you.

That said, it is decidedly not, as the dust-jacket cover proclaims, a “master class on the art and craft of songwriting.” I am not entirely sure what it is, though. It reads closer to something like one of Ricky Jay’s loquacious magic acts (or maybe Nabokov) than a work of musicology from someone like Greil Marcus or Peter Guralnick. So, in other words, I have spent this review trying to write about this book without falling into the obvious trap.

Or as Dylan would put it, “I didn’t know whether to duck or to run, so I ran.”

David Polansky is a Toronto-based writer and a research fellow with the Institute for Peace & Diplomacy. Find him at strangefrequencies.co.