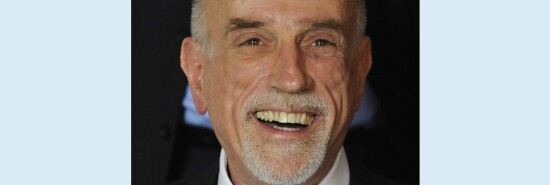

John E. Woods, 1942-2023

Daniel Ross Goodman

In Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and French, the word for “translation” — traduzione, traducción, tradução, traduction — is derived from the Latin root that also means “betrayal.” As lovely and welcoming as the Romance languages may sound, they have a more xenophobic aspect to them as well, implying that translation from their tongues into others is not really possible and that those who attempt it are committing an act of linguistic treason. Not so in German, wherein the word for “translation” is “Übersetzung,” which is derived from the Germanic words “over” and “placing,” and which can also mean “transmission.” In German, the act of translation is implied to be an undertaking of giving over, of conveying a concept, story, or saying from one language to another.

The irony in all this is that German is the most difficult to translate out of all of them. And it is all the more difficult to decipher when attempting to translate an author who writes in high literary German prose. Not so for John E. Woods, however, who made this oft-impossibly-seeming task look downright easy.

Woods, who died at 80, would have had an excellent translation career had his portfolio included only Günter Grass, Arno Schmidt, Patrick Süskind, Ingo Schulze, and the other 20th-century German literary authors he translated. His career became remarkable and earned him lasting literary fame when he set about translating the complete works of Thomas Mann.

In the first of his life pursuits that would oddly parallel Mann’s, Woods, who was born in Indianapolis and grew up in nearby Fort Wayne, studied at a Lutheran theological seminary in Pennsylvania (Mann was baptized as a Lutheran) before deciding to continue his theological studies in Mann’s native land. While learning German at the Goethe Institute, Woods married his German teacher, only to divorce her later when he revealed he was gay. Mann, who also married despite having been gay, or at least bisexual, was notorious for having struggled with his sexuality, though the public’s knowledge of the extent of these struggles came only after his death. Like Mann, Woods tried his hand at novel-writing, which did not prove to be to his liking. But his subsequent choice of translation would boomerang him back to Mann anyway. Additionally, like Mann, Woods moved from Germany to California, where he lived for many years before moving back to Europe, where he died in Berlin. (Mann died in Switzerland.)

While living in Amherst, Massachusetts, in 1976, Woods put away the novel he’d been fruitlessly working on, completed a translation of a German novel, Schmidt’s Abend mit Goldrand (Evening Edged in Gold), and sent the translation to a publisher. His translation was accepted, published, and won him an American Book Award, as well as the PEN Prize for translation. Woods would go on to win a variety of other awards for his translations, including another PEN Prize for his translation of Süskind’s Perfume, the Ungar German Translation Award in 1995, and the Goethe Medal in 2008.

No distinction would be as meaningful, however, as the esteem for which Woods would be held in the literary world for his translations of Mann. Mann’s perfectionist prose, though sublime in the original, had proven to be a particularly thorny linguistic code for translators to crack, with its layering of description upon description in swerving, multidirectional sentences that lingered on the page like leaves caught in a gust of wind, hovering in the air and refusing to come back to the Earth until they could perform one final twirl. Mann’s first English translator, H.T. Lowe-Porter, was roundly criticized for her overly stiff and formal translations of Mann and for other perceived errors.

When Woods applied himself to Mann, it was in the eyes of many as if an expert landscaper had set upon reviving a staid and dried-out royal garden: Woods cleared out the debris, improved the spacing between the shrubbery, and watered the grounds at just the right places, revealing the beauty that had always been latent in the soil but had simply needed the right hand to unearth. While Lowe-Porter is perhaps overly criticized, Woods nonetheless opened up Mann for countless new readers who may have otherwise thought the German writer was too old-fashioned, perhaps even staid and dried out.

In his translations, Woods, as he told an interviewer, tried “less [to] inhabit the text than inhabit universes.” Thanks to his translations of Mann, the entire English-speaking world is now able to dwell in Mann’s marvelous cosmos.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and the author, most recently, of Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Wonder and Religion in American Cinema.