P.J. O’Rourke’s riotous legacy

Rob Long

The great thing about a book of quotations is that you don’t have to read it from the beginning like a regular book. You’re actually supposed to skip around, to flip through the pages and stop where you stop.

This is an immensely appealing feature, especially for those of us suffering from middle-aged ADHD, a condition brought on by living in a culture that refuses to let you do anything for more than five minutes without interrupting you with a beep on your computer, a ding on your iPad, or a vibration from the phone in your pocket letting you know that there’s a push notification from a news website telling you that something important has happened in the lives of Harry and Meghan.

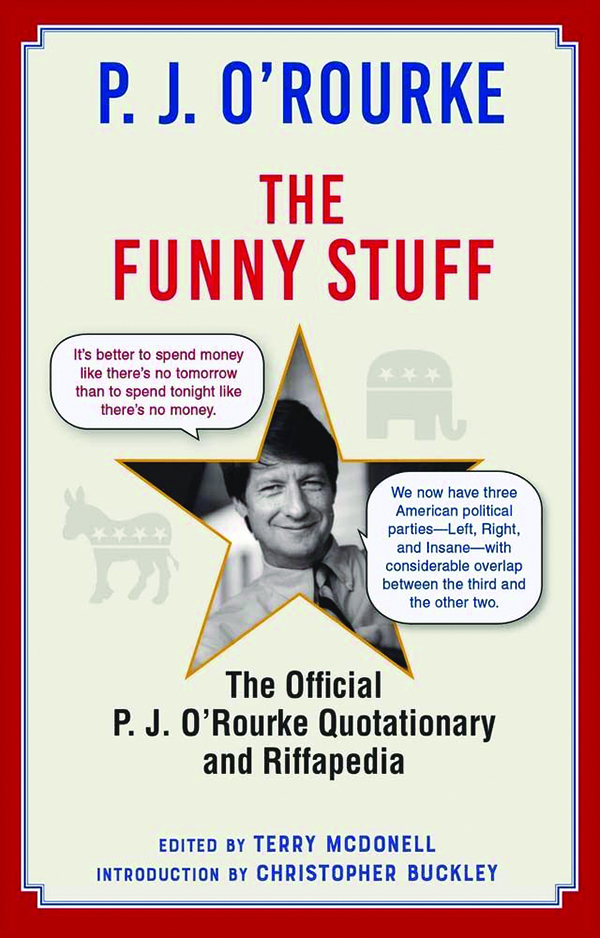

So I sat down with The Funny Stuff: The Official P.J. O’Rourke Quotationary and Riffapedia, a delightful, rapid-fire collection of some of the funniest and most sharply observed things ever written by the late journalist and author P.J. O’Rourke, which is to say some of the funniest and most sharply observed things ever written by anybody. And I just started to flip around.

First, though, I poured myself a drink. (He would have wanted me to.) And I sipped and flipped. On page 207: “Crypto-currency adds a kind of unwelcome mysticism to the already baffling material and philosophical aspects of money. Some regard the blockchain with almost religious awe, as if it were the work of mythical ‘Geek Gods’ high upon Mount Laptopus.”

And then a few pages later: “More obnoxious than a joke is a heated debate. Not only is it aggressive, but it violates the spirit of conversation as an art form. A conversation is not expected to ‘decide something’ any more than a painting by Matisse is.”

Another flip, maybe a splash more in the glass, and: “If wealth came from books I’d be too rich to be writing. I have no idea where power, success, and a big pile of money come from. Probably from someplace awful, such as hard work, or impossible, such as being much smarter than I am.”

I’m aware that there are things I probably should be doing — emails to respond to, push alerts to click on — but I’m having too much fun. A few pages on: “Self-loathing is one of those odd, illogical leaps of human intuition that is almost always correct.”

I was lucky enough to encounter O’Rourke in three distinct ways. The first, when I was about 12, he and some collaborators — including the future film director John Hughes, who went on to write and direct some of the biggest hits of the 1980s — published the most detailed and hilarious sendup of a small-town Sunday newspaper. National Lampoon Sunday Newspaper Parody is a nearly perfect replica of a newspaper — printed on newsprint, folded crosswise in sections — from a mythical town in Ohio. It’s a complex, interwoven piece of comic genius, with a genuine out-loud laugh in every column. Reading it and its companion volume, National Lampoon 1964 High School Yearbook Parody, filled me with a sense of possibility. It had never occurred to me that being funny on paper was an actual job. In a very real way, I have O’Rourke to thank for my career as a comedy writer. Without him, I might have thrown my life away and gone to law school.

When I was just out of college and embarking on the career that his National Lampoon parodies inspired, I encountered O’Rourke for the second time. By then, he had turned his talents to travel writing and political journalism, in which he lit up the pages with observations and adventures and — for me, a budding center/right comedy writer — a kind of fearlessness that was intoxicating.

Also, he wrote a lot about intoxicants, and when you’re in your early 20s, this seems impossibly glamorous.

His masterpieces of that period — especially Holidays in Hell, Republican Party Reptile, and the best book written about American politics ever, Parliament of Whores — are well represented in this new volume of snippets and quotations. Those books and everything else he wrote were filled with sharp verbal elbows and laugh-out-loud windups, brilliant observations packed into short little asides, and lovingly honest descriptions of the way people and governments actually work. Flipping through The Funny Stuff, especially with a drink in hand, going what we might call “the full-P.J.,” it’s almost like he’s in the room with you, delivering these words in his raspy, Ohio drawl.

Which brings me to the third way I encountered O’Rourke, which was in person. We met in the early 1990s in Los Angeles. As I recall, he was on a book tour — in those days, his output was such that he was nearly always on a book tour — and we became friends the way people in those days, before email and cellphones, became friends. We wrote a few notes to each other, ran into each other at various right-leaning events, and even spent a few months trying to figure out how to put Holidays in Hell onto the screen.

O’Rourke in real life was a lot like O’Rourke in the pages of The Funny Stuff and the rest of his work — funny, engaging, warmly appealing. But O’Rourke in real life was also different. In real life, he spent a lot of time listening, asking questions, watching, and observing. His work was funny and breezy and fast-paced, but the writer who produced that work was thoughtful and kind and often quiet.

I remember one night in particular. We had both contributed essays to a book called The Seven Deadly Virtues, and after a book event, we gathered somewhere — I think it might have been in someone’s office — to drink and gossip and shoot the breeze. There were a lot of other writers present, some fellow contributors, and some friends of O’Rourke’s. But there were also a few young writers just starting out, for whom the expectations for this evening were running high.

You could almost hear their thoughts: We’re hanging out with P.J. O’Rourke! This is going to be awesome!

And, of course, it was, but I think they were also surprised that O’Rourke wasn’t holding court. He wasn’t center stage, spinning tales and dropping hilarious, acid observations. He was talking and being funny (he was P. J. O’Rourke, after all), but he was also listening. O’Rourke was interested in the people and the world around him, which is maybe the reason his work — all of it, from the dead-on parodies of the early 1970s to the finely observed portraits of liberal readers of the Nation on a cruise in the old Soviet Union to the darkly funny political analysis of Parliament of Whores — rang with such truth. And the truth, as we all know, is the only thing that’s really funny. When we laugh — really laugh, belly-shaking and all — it’s only when we’ve heard something true. And to write the truth, you first need to pay attention.

The Funny Stuff captures a lot of O’Rourke’s dazzling and hilarious truth-telling, and it’s a nearly perfect book to flip through. But it will make you happy and sad at the same time. Happy because we have so much of O’Rourke’s light and laughter to enjoy. And sad because we’re not going to get any more.

Rob Long is a television writer and producer and the co-founder of Ricochet.com.