Fairfax County’s Library paid Nikole Hannah-Jones $35,000 to speak, then agreed to take the video of her speech down

Timothy P. Carney

Video Embed

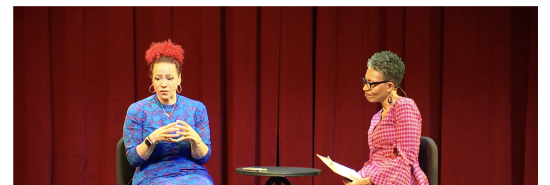

As of 9:00 Monday morning, you could still watch Nikole Hannah-Jones’ $35,000 conversation with the diversity officer of Fairfax County, Virginia. The county library system, which covered $29,000 of that speaking fee, plus the cost of her first-class airfare, drivers, security, and staff for the event, has agreed to take down the video today, two weeks after the event.

What’s more, the public library system, which is supposed to be dedicated to preserving and disseminating information, agreed to publish the video only as an unlisted YouTube video, and to send the link only to individuals who registered for the event.

So this taxpayer-funded conversation with a public figure is being treated as exclusive private affair by a public library system.

Hannah-Jones’ contract, signed on November 4 by the county library system and Hannah-Jones’s representatives, the Lavin Agency, prohibits any sort of recording. The contract states: “The presentation remains the intellectual property of Author. Library shall ensure that no portion of Author’s appearance at the Event is knowingly (i) recorded in any medium, including without limitation, on audio tape, video tape or film, or (ii) published, broadcast, or otherwise made available for streaming on the internet.”

Ted Kavich, a library administrator, wrote to Hannah-Jones’s representative Rakshitha Suresh on February 3, asking if recording would be possible. At this point, the library system still expected Hannah-Jones to deliver a speech followed by Q&A. “Staff at the county’s Channel 16 would like to be on-site to tape the event — just Ms. Hannah-Jones’ talk, not the Q&A that follows,” Kavich wrote. “Is this a possibility? I know this would certainly require permission from her and you, if it is possible at all (I’m not sure if there is already a ‘no recording’ note in the contract?). Channel 16 would broadcast the event on their public access channel and the channel’s online stream, and they could of course follow whatever restrictions were imposed (only air for “x” days, etc.).”

Kavich’s colleague, Renee Edwards, program director for Fairfax County Public Library, proposed a very limited recording and publication in a Feb. 9 email to Suresh. “I suggested that we can temporarily upload an unlisted video to YouTube and share with people on the main and wait lists,” Edwards wrote. “We can leave it up for about two weeks and then archive it.”

Suresh accepted the offer that day, adding one additional restriction: The video could remain archived for only 30 days:

“Great news, we have a go on the recording,” wrote Suresh. “Provided, it is on YouTube as an unlisted video for no longer than 2 weeks from the date of the event and is accessible only to registered participants of the event. Can stay archived for a period of 30 days.”

Suresh specified in a later email: “The whole idea is that the video is not up and open to anyone searching on the web for it.” Edwards replied, “It won’t be! I promise.”

Suresh replied with “I trust you” and a smiley face. Edwards replied with a heart.

Throughout the hour-long conversation on stage in McLean, Virginia, Hannah-Jones repeatedly spoke about “why these conversations are so important,” and asserted a crucial need for public discussions about race, slavery, and America’s history.

Her insistence that publicly funded, library-hosted discussions of the video be hidden from the public does not seem in keeping with that urgency.