A biography of literary wives

Malcolm Forbes

In many cases, the literary wife is in fact a literary midwife, a valuable helpmate whose care and attention pull books out to see the light of day. Several male writers have depended entirely on their wives. Vladimir Nabokov could devote himself to his writing because his wife, Vera, devoted herself to him. For over five decades, her duties ranged from negotiating his contracts and typing his manuscripts to licking his stamps and cutting his food. Vera was also instrumental in securing her husband’s literary reputation by stopping him from burning an early manuscript of Lolita and rescuing charred pages from the flames.

And then there are the writer wives who have unwittingly helped their writer husbands. Robert Lowell infamously incorporated Elizabeth Hardwick’s heartfelt private letters to him into poems for The Dolphin. F. Scott Fitzgerald was accused by Zelda of using a portion of her diary for The Beautiful and Damned. “Mr. Fitzgerald,” she wrote in a review of the book, “seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

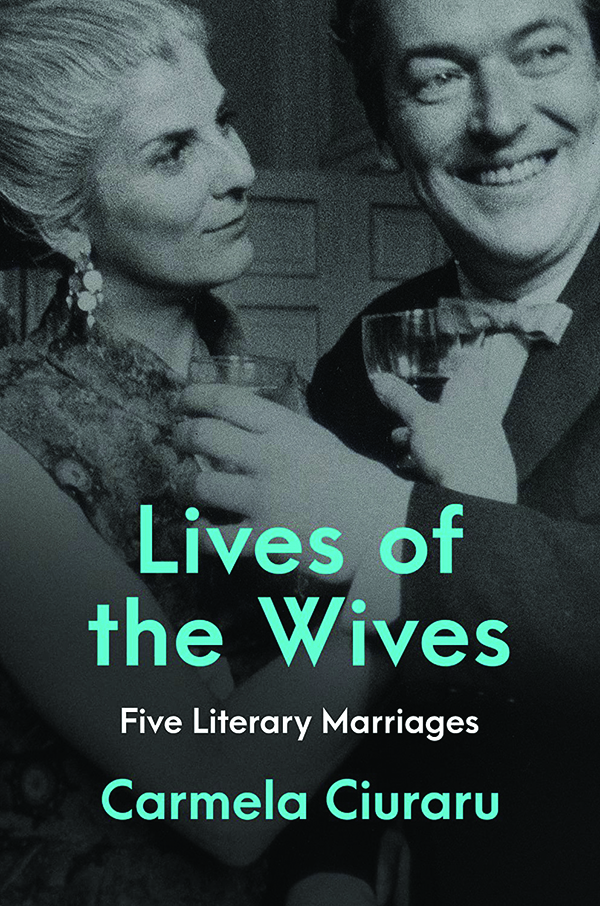

A new book tells the stories of five remarkable women who played a crucial role in the careers of their literary partners. At first glance, it isn’t clear what Carmela Ciuraru’s focus is: Her title, Lives of the Wives, appears to offer something different from that of her subtitle, “Five Literary Marriages.” It gradually becomes clear that Ciuraru sets out to cover both, with each of her sections comprising a potted biography of a significant other and a study of their less-than-smooth or downright rocky marital relations. The history of wives, according to Ciuraru, is predominantly one of fortitude and forbearance: “Toss in male privilege, ruthless ambition, narcissism, misogyny, infidelity, alcoholism, and a mood disorder or two, and it’s easy to understand why the marriages of so many famous writers have been stormy, short-lived, and mutually destructive.”

Refreshingly, Ciuraru eschews the usual suspects from the “all-star wifely roster” — no Vera or Zelda, no Nora Barnacle or Sofia Tolstoy. She also omits the many women who paid an even higher price as wives, those used and abused by the much-married Ernest Hemingway, Saul Bellow, and Norman Mailer. The women who Ciuraru does center upon are known entities, most of them famous in their own right, but by presenting them in the context of marriage, she allows us to see them, and their partners, in a brilliant new light.

Lives of the Wives is at its most absorbing when Ciuraru highlights the rough and the smooth of each of her chosen “asymmetrical partnerships.” It is cheering to learn of downtrodden and browbeaten women breaking free from their designated roles and asserting their authority by following their own agenda or having their own success.

Ciuraru opens with the book’s only same-sex couple, Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall. In London in 1915, three years after an undistinguished first encounter, the pair met at an afternoon tea party and experienced “love at second sight.” Troubridge, a sculptor, was married to a high-ranking naval officer but deplored her wifely responsibilities and felt constrained by her social obligations. Hall, who dressed dapperly in tailored men’s suits and went by the name of John, was in a relationship with an older woman. Ciuraru reveals that when Troubridge and Hall became a couple, the former willingly assumed the role of “submissive wife” and the latter “controlling husband.” Troubridge made the supreme sacrifice by shelving her own creative aspirations to build, support, and even promote her lover’s writing.

For nearly 30 years, Troubridge assisted Hall at every turn, living what she called “a life of watching, serving and subordinating everything in existence to the requirements of an overwhelming literary inspiration and industry.” As an editor, she went the extra mile by changing Hall’s humdrum book titles to something more intriguing. (It is thanks to Troubridge that Hall’s most famous novel is called The Well of Loneliness and not Stephen.) Hall repaid her by breaking her heart and becoming obsessed with a younger woman.

Ciuraru informs her reader at the outset that these two lesbians are “the most conventional — and socially and politically conservative — couple in Lives of the Wives.” She isn’t wrong. Her second section charts the shared history of the Italian novelists Elsa Morante and Alberto Moravia, two people who bonded through their artistic circle of friends and their abhorrence of fascism — and little else. Neither felt a strong sexual attraction to the other. He spoke openly about his life and work, she was fiercely private. She was also mean-spirited, thriving on friction and frequently putting him down in public. She claimed, “Literary couples are a plague.” He described her as “an angel fallen from heaven into the practical hell of daily living. But an angel armed with a pen.” That pen produced great literature, but the hell of daily living took its toll and deepened the cracks in a crumbling marriage.

Relations turn truly toxic in Ciuraru’s next chapter. Mere months after meeting in London, American actress Elaine Dundy and British theater critic Kenneth Tynan tied the knot. As Tynan proceeded to make his name and leave his mark as the most feared and revered reviewer of his day, the pair became a golden couple who routinely lost themselves in a giddy social whirl, mingling with the likes of Gene Kelly, Humphrey Bogart, Katherine Hepburn, and “Tenn” Williams.

Clouds gathered when Dundy upped her alcohol intake to cope with Tynan’s demands, both as a writer and husband. He was a short-tempered, self-centered tyrant, manipulator, and “spanking addict” prone to angry threats and violent outbursts. (“Ken and I disagreed about a play,” she told a friend when she turned up at her door one night, her dress covered in spaghetti.) But it wasn’t until 1958 that Dundy fully experienced the full extent of her husband’s wrath. She published a comic novel, The Dud Avocado, to rave reviews. Tynan, in a fit of jealousy and anger, warned her that if she ever dared to write a follow-up, he would divorce her. Undaunted, Dundy sat down the next morning and started writing.

Not all of Ciuraru’s stories are so involving. Her shortest chapter on Elizabeth Jane Howard and Kingsley Amis proves distinctly underwhelming. Howard did everything for Amis in their “hierarchical relationship,” busying herself with domestic chores and secretarial jobs (and never nagging him about his drinking), and only truly found the time, energy, and confidence to devote herself to her own writing when she left him. Howard’s crowning literary achievement, the exquisite quintet of novels known as the “Cazalet Chronicles,” is mentioned in a few cursory lines at the end of Ciuraru’s extended sketch. In this, her centenary year, Howard deserves a better appraisal.

Otherwise, Ciuraru excels with her “project of reclamation and reparation.” It is cheering to learn of downtrodden and browbeaten women breaking free from their designated roles and asserting their authority by following their own agenda or having their own success. In each case, she skillfully manages to “reposition” her wives, bringing them out from behind their great men and placing them center stage. Up close, we discern their resilience and determination and view most of them not as other halves but better halves.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.