China and the noble lie

Sean Durns

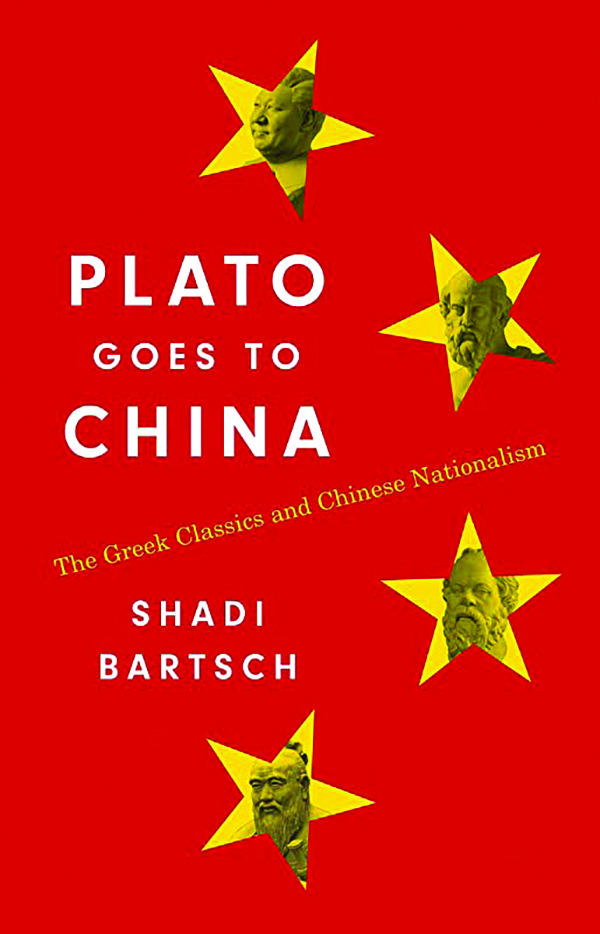

Antiquity’s “dead white men” may have fallen out of favor on woke campuses, but philosophy is thriving in the Middle Kingdom. In her new book, Plato Goes to China: The Greek Classics and Chinese Nationalism, the scholar Shadi Bartsch examines the role of Greek classics in China, an overlooked area of study. An award-winning classicist and professor at the University of Chicago, Bartsch offers a revelatory look at how China uses, and sometimes abuses, classical thought.

“The impetus for the study,” Bartsch notes, “was to learn in what ways the Chinese and their culture are different readers” of the foundational texts that “lie behind western concepts of individuals, citizens, politics, rationality, and even morality.” In the West, the study of Greek classics is, of course, colored by the biases and background of the reader. By seeking to understand how the Chinese approach these texts, Bartsch hopes to “break out of this hall of mirrors, to see how the categories and assumptions of this tradition were not universal.” What she finds, however, is arguably a hall of mirrors of its own — at times, even a carnival fun house.

And the distortions start at the very beginning, with the first known introduction of Greek thought to China. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it begins with Christian missionaries, who have played a long and often remarkable role in Chinese history. For centuries, China was largely closed to the West. But in 1601, an Italian Jesuit from Rome named Matteo Ricci was finally invited to enter the Forbidden City in Beijing. The emperor had hoped that Ricci would offer insights into astronomy. Ricci, of course, had other plans.

The small group of Christian missionaries who were allowed in quickly learned to disguise their intentions — and, to an extent, themselves. They learned to read classical Chinese and to speak Mandarin. And they discovered it was in their interest to dress like Confucian scholars instead of lowly Buddhists. As a result, they had access to the small group of court scholars, at times even engaging in debates with Confucian scholars.

But, as Bartsch notes, the Jesuits “faced a roadblock.” The Chinese elite was not interested in the tenets of Catholicism. The Chinese scholars looked down on what they considered to be “barbarians.” And so the Jesuits responded with some deception.

“They had already become virtual Mandarins,” Bartsch writes, “putting on the garb of Confucian scholars and learning Confucian teaching in order to engage the Chinese scholars at court.” They also learned to use Confucian terminology to translate items and categories to the court. Slowly, they “developed a method to make Christianity more palatable to the Confucians: they passed it through the sieve of the pre-Christian west, and specifically through Aristotle and the Stoic teachings of the Greek ex-slave Epictetus.” Ricci himself proved “remarkably proficient at presenting Stoicism as a sort of Christianity.”

Accordingly, the first known transmissions of Greek philosophy to the Chinese were, from the very beginning, necessarily selective and replete with self-censorship. This “ends justify the means” approach to the Greek classics would prove to be a theme.

Most of Plato Goes to China focuses on a brief, albeit tumultuous, period in Chinese history, running from roughly 1890 to 2000. In that hundred-year span, China would experience the end of dynastic rule, a short-lived republic, internecine conflict that lasted decades, invasion from foreign powers, multiple wars, and the installation of what would become the largest and longest-lasting dictatorship in modern history. Suffice it to say: That is a lot to endure in a comparatively short period of time. And within China itself, the classics would experience their own death and rebirth.

The social upheaval that engulfed China in the late 19th century led to calls for political change, as a growing number of Chinese felt that the Qing dynasty was losing its luster. Foreign-educated Chinese played a key role in these opposition movements, and many were influenced by the thinkers of antiquity. “China’s young intellectuals and reformers clamored for a new, republican China with radically different values,” Bartsch writes. In searching for an alternative to dynastic rule, many of them looked to Aristotle’s Politics and other Greek philosophical and political writings. Chinese translations were hard to come by. Many had to rely on Japanese versions to explore the Greco-Roman tradition.

Among the most influential was the essayist Liang Qichao, who translated Aristotle while living in exile in Japan. Aristotle, Liang told his readers, “is truly the singular representative of ancient civilization.” Among the many ideas that Liang was most enthralled with was the concept of citizenship. As Bartsch notes: “For many Chinese, ‘the citizen’ was a completely new idea. Although theorists of western politics from Aristotle and Cicero to Machiavelli had all emphasized the importance of political participation, the traditional Confucians considered personal moral development and familial duty as far more important human responsibilities.”

Accordingly, by commending Aristotle’s idea of the citizen, Liang was “going against the grain of thousands of years of tradition, both with the idea of the citizen and with the further explanation that the citizen had the right and even the duty to participate in the state’s legislative, executive and judicial processes.” China, Bartsch observes, “had no parallels to such ideas.”

Liang hoped that his promotion of the Greek classics would lead to reform. Yet, while they did play an important role in the May Fourth Movement that erupted in 1919, such hopes were forlorn.

When Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party seized power in 1949, another sea change occurred. A butcher of men, Mao fancied himself a poet and a philosopher. He was also avowedly anti-Western, squelching out the teachings of both Confucius, whose works he associated with dynastic rule, and Plato alike. Ironically, as a young man, Mao admired Liang. But by 1941, the dictator-to-be was criticizing intellectuals who “cited the Greeks whenever they spoke.”

The post-Mao era witnessed a renewed interest in Greek learning, with a bevy of Chinese scholars studying the subject. Some of their works inspired a Chinese TV documentary called River Elegy. Broadcast in six parts in 1988, the documentary expressed an openness to Western culture that would prove tragically short-lived.

The events at Tiananmen Square in 1989, in which government forces massacred an untold number of protesters, also killed the study of Greco-Roman thought. The government denounced River Elegy as “spiritual pollution,” and several of the documentary’s screenwriters fled, doomed to live in exile. “No more would reform-minded twentieth-century Chinese readers of western classical texts turn to the Greek classics as a source for the values — and successes — of modern western civilization” or as a “way of introducing the concepts of individualism, citizenship and liberty to China.”

Instead, in the post-Tiananmen era, the classics would often be used as a means to critique the West. Bucking Mao, Chinese ruler Xi Jinping would cite Confucius. However, Plato et al. would be treated in an entirely different manner. Just as the May Fourth Movement had turned Aristotle into a pro-democracy advocate, some Chinese scholars have, in recent years, used the classics to savage the United States.

Bartsch’s book explores these twists and turns. This is not a dry, academic textbook about philosophy. Like Plato’s dialogues themselves, it breathes with drama. Plato Goes to China examines how classical Western texts have been used as a battleground for debates that resonate across both continents and time. And she does so with a level of humility and curiosity that honors all of our intellectual ancestors.

Sean Durns is a Washington, D.C.-based foreign affairs analyst.